Although they will initially pay $553 million in taxes, the partners will get that back, and about $200 million more, from the government over the long term.

The plan, laid out in the fine print of Blackstone’s financial documents, comes as Congress debates how much managers at private equity firms like Blackstone and hedge funds should pay in taxes on their compensation.

Lee Sheppard, a tax lawyer who critiques deals for Tax Notes magazine and has studied the Blackstone arrangement, said it was a reminder of the disconnect between the tax debate in Congress and how the tax system actually operates at the highest levels of the economy.

“These guys have figured out how to turn paying taxes into an annuity,” Ms. Sheppard said. “What people don’t realize is that the private equity managers, the investment bankers, all the financial intermediaries, are in control of their own taxation and so the debate in Washington about what tax rate to pay misses the big picture.”

The debate in Congress is about whether most of the compensation that fund managers earn should be taxed at the 35 percent rate that applies to other highly paid Americans, or at the 15 percent rate for capital gains.

Questions in Congress about possibly raising taxes on such compensation were prompted in part by publicity about the rich rewards for people who run these firms. Stephen A. Schwarzman, the co-founder of the Blackstone Group, made nearly $400 million last year, for example.

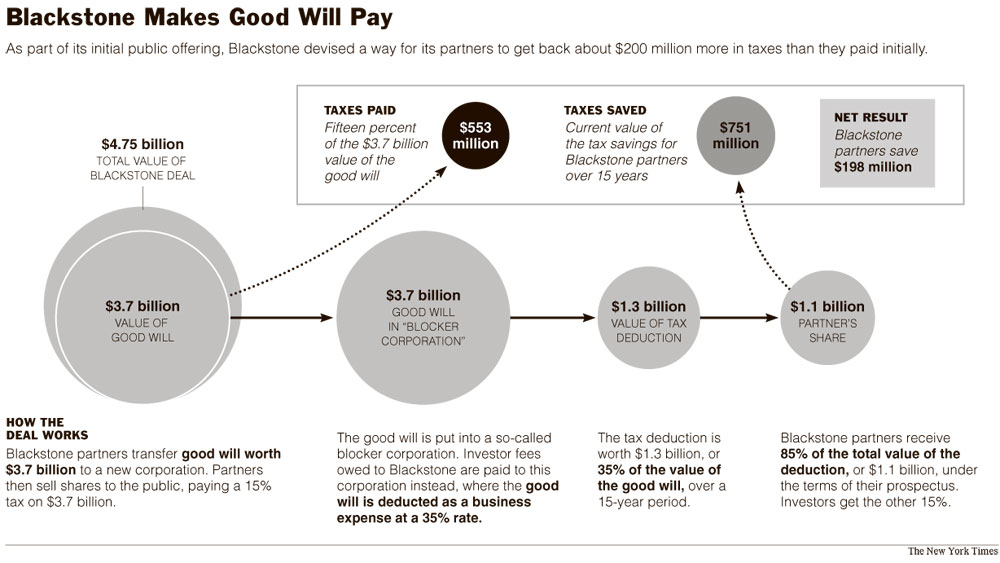

The Blackstone partners’ tax deal, however, is for the sale of part of their stake in the management firm, which is why their profits were taxed at the usual 15 percent tax rate for capital gains. Over all, the company raised $4.75 billion in the initial public offering, but the benefits of the tax structure involve just $3.7 billion of that.

Other private equity firms and hedge funds that have gone public, or plan to, make use of similar techniques, their documents show.

The Fortress Investment Group, which went public in February, uses a form of this tax structure. Two funds that plan to go public soon, Kohlberg Kravis Roberts and Och-Ziff Capital Management, describe similar tax strategies in their preliminary disclosure documents.

All three firms declined to comment. However, several tax lawyers, who could not be quoted by name because their firms had restricted them from making public comments on these issues, agreed in principle with the analysis of the tax structure’s implications.

No Blackstone official would speak for attribution. A spokesman, who insisted on not being identified, said only that such an analysis of the tax implications of Blackstone’s deal was “totally flawed.”

A report issued this week by the Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation indicated that such deals had been done at other companies.

Victor Fleischer, a law professor at the University of Illinois, came to a similar conclusion as Ms. Sheppard after studying the Blackstone deal.

Blackstone’s tax maneuver hinges on its use of good will, an accounting term for the value of the intangible assets, like a well-known brand name, that are built up by a company over time. That value is part of the reason a company is worth more than the sum of its physical parts, like buildings and equipment.

Individuals who create good will cannot deduct it. But when good will is sold the new owners can because its value is assumed to erode. The Blackstone partners sold the good will from their left pocket to their right.

In simplest terms, the Blackstone partners paid a 15 percent capital gains rate on the shares they sold last month in the initial stock offering to outside investors (those shares represented a stake in the Blackstone management company, not its funds).

Blackstone then arranged to get deductions for itself for the $3.7 billion worth of good will at a 35 percent rate. This is a twist on the “buy low, sell high” stock market adage; in this case it would be “tax low, deduct high.”

The deductions must be spread out over 15 years. And the original Blackstone partners are getting just 85 percent of the tax savings, leaving the other 15 percent to outside investors. The deductions on the $3.7 billion to the partners are $1.1 billion over 15 years.

If these tax savings were paid as a lump sum this year, the partners would get about $751 million, which is $198 million more than the taxes the partners will pay on the $3.7 billion of good will.

The lump-sum value was done using the rate set by the Internal Revenue Service for deals lasting 15 years.

Officials at one hedge fund suggested that a rate three times that set by the government should be used to calculate the long-term economics because many hedge funds and private equity firms earn high rates of return. Applying this interest rate, 15 percent, still results in a net tax of $175 million for the Blackstone partners, or less than 5 percent.

How can those deductions be worth almost as much, or more, than the taxes paid?

The ability to provide answers to such questions is why tax lawyers can typically charge $700 an hour or more. Just as fashion designers blend textures, colors and shapes, tax experts mix and match elements of partnerships and corporations, and bits and pieces of the tax code, securities laws, accounting rules and economics principles.

The tax maneuver starts with Blackstone partners selling to a newly created subsidiary corporation $3.7 billion worth of good will. Such entities are known within the tax trade as blocker corporations, because they help block taxes from reaching the Treasury.

Here is how the structure works: Blackstone can deduct 35 percent, based on the corporate tax rate for depreciation, of the value of $3.7 billion in good will, or $1.3 billion. Because the partners told investors they have the right to 85 percent of that amount, that means they have $1.1 billion worth of deductions.

That amount would be saved over 15 years. But for an apples-to-apples comparison with the taxes it pays on the proceeds this year, the value of $1.1 billion in today’s dollars is $751 million.

Compared with the $553 million tax paid, the Blackstone partners will get back $198 million more than they paid in taxes.

To reap those savings from the deductions, Blackstone needs to funnel income into that blocker corporation.

So Blackstone directs to the corporation the annual fees it receives from investors for managing their money, which is 2 percent of the assets they manage. Those fees totaled more than $850 million last year, far more than the amount needed to write off the good will.