GM bug activates cancer drug

Bacteria target medicine to shrivel

mouse tumours.

22 April 2004

HELEN R. PILCHER

|

|

|

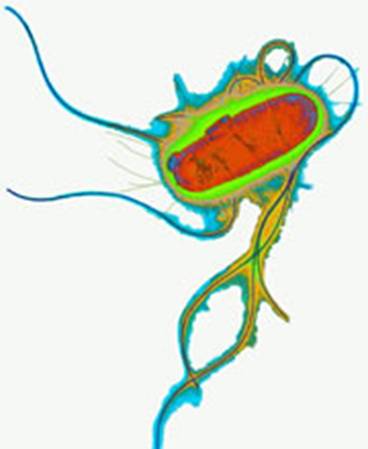

E. Coli

carry a key protein deep inside the cancer cells. |

|

© SPL |

|

|

Genetically engineered bacteria could help fight cancer. In mice

at least, modified bugs have been used to prime tumour cells to

respond to anti-cancer drugs, killing the cells and shrinking

tumours.

Georges Vassaux from the Hammersmith Hospital, London, and his

colleagues injected mouse tumours with an altered form of

Escherichia coli, a bacterium that sometimes causes food

poisoning. The DNA in the bacteria was modified to allow them to

enter cells.

The mice were then injected with cancer drug 6-MPDR. This drug is

inactive and has no effect on its own, but one of the bacteria's

naturally occurring enzymes turns the medicine into a potent toxin.

The treatment killed cancer cells in the area where the drug had

been activated and left surrounding tissue unharmed. Three weeks

later the tumours had shrunk by up to two-thirds and most of the

remaining cells were dead, the team report in Gene Therapy1.

Such a targeted effect is an improvement on standard chemotherapy

treatments, which can damage healthy as well as cancerous tissue,

says Vassaux.

Although human trials are a long way off, the technique looks

most promising for isolated cancers that have not spread, such as

head and neck tumours. The method could be used to reduce tumours

before surgery; it might also prevent their recurrence.

"We think that introducing bacteria into a patient's body, albeit

harmless, neutered ones, will provoke the immune system and help to

direct it against the tumour," says Vassaux. This could prime the

body to destroy any cancerous cells left behind by surgery and

prevent secondary tumours from forming.

Bacterial invasion

The team added two new genes to their E. coli bacteria.

One, called inv, makes a protein that helps the bacteria

penetrate human cells. The second, hly, helps the bugs spill

their contents, releasing the drug-activating enzyme.

"It is an interesting idea," says Nigel Minton from Nottingham

University, UK, who studies the anti-cancer potential of bacteria.

But he points out that other groups, including his own, are

attempting to get similar results without the need for genetic

modification.

Spore-forming bacteria, such as the food-poisoning culprit

Clostridium, could also be used to deliver the critical enzyme

to tumours, he says. If the spores are injected they disperse around

the body and germinate in oxygen-poor areas, such as tumours,

releasing the enzyme. When the inactive cancer drug is added, it is

kicked into action and mouse tumours shrink.

In this case, the bacteria do not enter the actual tumour cells,

but they release their contents nearby.

Using bacteria to target cancer cells is an innovative tactic,

says Robert Souhami, director of clinical research at Cancer

Research UK in London. "Developing new drugs tends to grab the

headlines, but equally important is the development of efficient

systems to deliver treatments to cancer cells." |