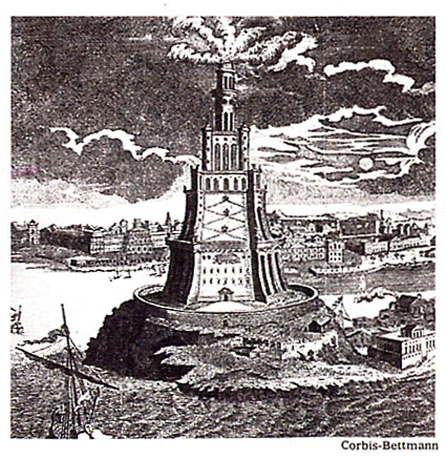

| ATLANTIS -- The most famous lost city of all, right, it probably never was. Plato described ''a temple to Poseidon himself, the outside covered all over in silver.''; |

|

The New York Times, Sept 6, 2005 pF5(L)

Vanished, Under Force of Time and an Inconstant Earth. (Science Desk) Dennis Overbye.

Full Text: COPYRIGHT 2005 The New York Times Company

Nothing lasts forever. Just ask Ozymandias, or Nate Fisher.

Only the wind inhabits the cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde in Colorado, birds and vines the pyramids of the Maya. Sand and silence have swallowed the clamors of frankincense traders and camels in the old desert center of Ubar. Troy was buried for centuries before it was uncovered. Parts of the Great Library of Alexandria, center of learning in the ancient world, might be sleeping with the fishes, off Egypt's coast in the Mediterranean.

''Cities rise and fall depending on what made them go in the first place,'' said Peirce Lewis, an expert on the history of New Orleans and an emeritus professor of geography at Pennsylvania State University.

Changes in climate can make a friendly place less welcoming. Catastrophes like volcanoes or giant earthquakes can kill a city quickly. Political or economic shifts can strand what was once a thriving metropolis in a slow death of irrelevance. After the Mississippi River flood of 1993, the residents of Valmeyer, Ill., voted to move their entire town two miles east to higher ground.

What will happen to New Orleans now, in the wake of floods and death and violence, is hard to know. But watching the city fill up like a bathtub, with half a million people forced to leave, it has been hard not to think of other places that have fallen to time and the inconstant earth.

Some of them have grown larger in death than they ever were in life.

Take the library in Alexandria. If anyplace might have had justifiable pretensions of permanence it would have been the library, founded sometime around 300 B.C. It grew under the early Ptolemaic rulers of Egypt into an enduring symbol of culture and knowledge before disappearing into the sand and sea less than 1,000 years later.

| ''This was the library,'' said Roger Bagnall, a historian at Columbia. ''It influenced everybody who ever thought about building a library.'' Nobody, Dr. Bagnall complains, knows how large it was -- estimates range from 40,000 to 400,000 scrolls -- or what was actually in it. The library's demise is equally shrouded in myth. One legend says the books burned during Caesar's conquest of Alexandria in 47 B.C., but the library was still around in the fourth century, according to historical accounts. Dr. Bagnall thinks that simple neglect killed the library. ''Books rot,'' even acid-free papyruses, he said, noting that there are no records of any investment in maintaining the library after the early Ptolemies. By the time Christian mobs sacked the library and museum at the end of the century as a pagan institution, there was probably little left to destroy. ''The palace quarter was pretty well wrecked by that point. Whatever had survived the rotting didn't make it past that,'' Dr. Bagnall said. Later, in 642, the Arabs moved Egypt's capital to the Cairo region and Alexandria shrank into obscurity.

|

|

''This was the library,'' said Roger Bagnall, a historian at Columbia. ''It influenced everybody who ever thought about building a library.''

Nobody, Dr. Bagnall complains, knows how large it was -- estimates range from 40,000 to 400,000 scrolls -- or what was actually in it. The library's demise is equally shrouded in myth. One legend says the books burned during Caesar's conquest of Alexandria in 47 B.C., but the library was still around in the fourth century, according to historical accounts. Dr. Bagnall thinks that simple neglect killed the library. ''Books rot,'' even acid-free papyruses, he said, noting that there are no records of any investment in maintaining the library after the early Ptolemies.

By the time Christian mobs sacked the library and museum at the end of the century as a pagan institution, there was probably little left to destroy. ''The palace quarter was pretty well wrecked by that point. Whatever had survived the rotting didn't make it past that,'' Dr. Bagnall said. Later, in 642, the Arabs moved Egypt's capital to the Cairo region and Alexandria shrank into obscurity.

| On the other side of the globe, in the Caroline

Islands of Micronesia, a stony silence relieved only by the lapping of waves

envelops the empty city of Nan Madol. It consists of almost 100 islands,

built by humans and constructed of columns of basalt 15 feet long and

weighing 5 tons, stacked log cabin style to make walls 25 feet high.

Local legend says that you will die if you spend the night there. But once this was home to the nobles and priests of the Saudeleur dynasty, which ruled Pohnpei's 30,000 inhabitants up until about 500 years ago, according to William S. Ayres, an archaeologist at the University of Oregon. Dr. Ayres said that Nan Madol was constructed out on the reef, starting about 1,500 years ago, partly because people had been living out there for hundreds of years to have easy access to the sea, and, perhaps more important, to better commune with ocean deities.

|

|

|

| Nan Madol structures, Micronesia | ||

| The columns for the walls were quarried on

Pohnpei, he said, and floated out to the reef on rafts, about 500,000 tons

in all over the 1,000 years of construction, Dr. Ayres has estimated. While

most of the islands were living quarters for priests, others were given over

to special purposes like making canoes, preparing coconut oil or, most

grandly, burying royalty in tombs with courtyards surrounded by 25-foot

walls.

Nan Madol's end was simple. When the last of the Saudeleurs was overthrown, the island was divided into smaller chiefdoms, ''which exist up to the present day,'' Dr. Ayres said. The city was abandoned to its sleeping kings and its cold stone logs.

|

|

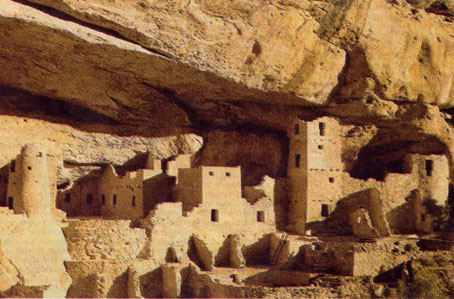

The dry, desert silence in Mesa Verde tells a more complex tale. Archaeologists say that in the middle of the 12th century, some 20,000 people were living in the picturesque cliff dwellings and surrounding areas in southwestern Colorado, growing maize, squash and beans, raising turkeys, and apparently fighting with their enemies (thus the cliff houses, which were easier to defend than mesa-top villages).

By 1300, these Anasazi, or ''ancient ones,'' were all gone.

| That crash was due to a combination of climatic, political

and environmental factors, according to Tim Kohler, an anthropologist at

Washington State University, who along with Mark Varien of the Crow Canyon

Archaeological Center in Cortez, Colo., has been studying the history of

pueblo populations. One culprit was climate change.

According to classic tree-ring studies by Andrew Ellicott Douglas of the University of Arizona, the years 1275 to 1295 were abnormally dry. Recent work using bristlecone pine tree rings has established that it got cold, as well, during that period, lowering the maize production even more, Dr. Kohler said. At the same time, the deer population seems to have declined significantly. As a result they needed the turkeys for protein. And what were they feeding the turkeys? Corn. ''If something happens to the maize, the system collapses,'' Dr. Kohler said. |

|

|

| And so it did. Adding to the pressure, apparently, was war, which meant that the people of Mesa Verde were penned in. They didn't or couldn't spread out to less protected areas. Instead they simply left. The green table had turned brown, and perhaps red. | MESA VERDE -- From 600 A.D. to 1300 A.D., people lived in the area of the present-day Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado, right. Archaeologists say that in the middle of the 12th century some 20,000 people lived in the picturesque cliff dwellings and surrounding areas. |

The most famous lost city of all is one that probably never really existed, Atlantis, the fabulous island civilization swallowed by the sea, which was referred to by Plato.

Some scholars think he might have been inspired by one or more real events. Among them is the destruction of Helike, a city on the Corinthian coast, which was swallowed by an earthquake and a tsunami one winter night in 373 B.C., during Plato's lifetime. ''For the sea was raised by an earthquake,'' wrote the Greek geographer Strabo, ''and it submerged Helike and the Helikonian Poseidon.'' The city went down like the Titanic with its entire population on board. An expeditionary force sent from a nearby town the next day found no survivors and no bodies to recover.

Though not the seat of empire like fabled Atlantis, Helike was a significant and prosperous city. It was the head of a confederacy of 12 Greek city states, the First Achaean League, whose successor, the Second Achaean League, was recommended as a model of federalism by Alexander Hamilton and James Madison in their Federalist Papers. It minted its own coins.

Lured by the prospect of an underwater time capsule, archaeologists have long sought the remains of the sunken city. Five years ago, after a dozen years of searching, a team of archaeologists led by Dora Katsonopoulou of the Ancient Helike Society in Aigion, Greece, and Steven Soter, a geophysicist with New York University's Center for Ancient Studies, said they had found the lost city -- not in the sea but on the coastal plain next to it, near Aigion, about 45 miles northwest of Corinth. It may have been gradually raised by seismic activity, said Dr. Soter. Moreover, he said, three rivers feeding the coastal plain deposit sediment that helps build it up.

In expeditions every summer, Dr. Soter and his colleagues have uncovered more and more of the city, including a road that goes almost a mile across the plain, walls, buildings, coins, pottery and a cemetery, although they have not found the center of the city yet.

Recently they have found a whole new and unknown city, dating from 2200 B.C., the early Bronze Age, near Helike. The sediments of this ruin contain marine and lagoonal microfauna, Dr. Soter said, suggesting that it too, may have been swallowed by an earthquake and a tidal wave like Helike, but 2,000 years earlier, only to rise again. It may be, he said, that there have been recurrent floods and abandonments on the plain, the land rising and sinking, cities blooming out of the reborn mud.

''Good agricultural land tends to be reoccupied after catastrophes,'' Dr. Soter said, echoing Dr. Lewis's statement. ''People will live there and take their chances.''

There is in the picture a kind of immortality for the dead, as well as for the perennials blooming on the flood plain. If Helike can give rise to the vision of an Atlantis, a collection of scrolls can forever change our concept of learning and memory and empty stones can inspire us to reveries, what can we expect from jazz, gumbo and soft air at one of the trading crossroads of the world, so blessed and cursed with water?

New Orleans will never die. It is already larger than life.

| TROY -- A Greek force pretended to abandon its siege of Troy, leaving behind a large wooden horse at the gates of the city -- according to the lore. The Tojans pulled the horse into the city, unaware that Greek soldiers were hidden inside. After nightfall Greeks dropped down from the horse, opened the gates of the city to their waiting compatriots who sacked Troy. The city was buried for centuries before it was uncovered. |  |

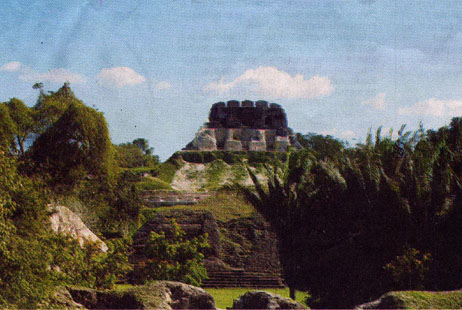

The demise of the Mayan empire, including the city of Xunantunich, (below) lacks a coherent, prevailing theory among historians. For a brief article and timeline click here.

| SAN IGNACIO -- The Castle of the Xunantunich Mayan ruins, left, outside San Ignacio, Belize, in 2002. The ruins rise 130 feet above a main plaza. |

|