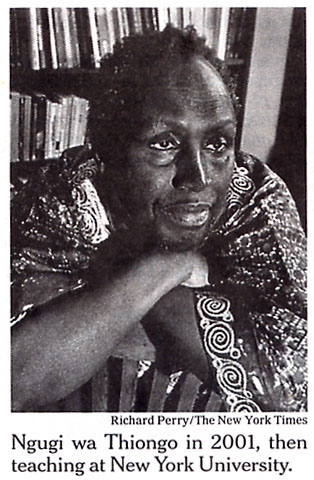

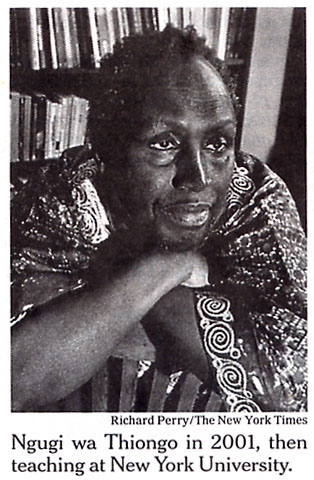

The New York Times, August 16, 2004 pA4

A Literary Lion Returns to a New, Still Dangerous,

Kenya. (Foreign Desk) Marc

Lacey.

Full Text: COPYRIGHT 2004 The New York Times Company

In ''Homecoming,'' a collection of essays published 30 years ago, Ngugi wa

Thiongo assessed various forms of violence, some of which he considered

justified to achieve social ends and some of which he dismissed as just plain

thuggery.

''Violence in order to change an intolerable, unjust social order is not

savagery: it purifies man,'' he wrote in defense of Kenya's sometimes violent

struggle that led to independence from Britain in 1963.

Mr. Ngugi, who returned to Kenya last month after 22 years of exile, is in

the midst of a remarkable homecoming of his own, one that he says has inspired

him but saddened him, too. He has been given a hero's welcome and has seen the

political progress that Kenya has made. But Mr. Ngugi (pronounced GOO-ghee) has

also experienced Kenya's new challenges -- violent crime and corruption chief

among them.

| On Wednesday night, while Mr. Ngugi was resting in a Nairobi

apartment between speaking engagements, four robbers barged in and

brutalized him, his wife and a friend. The attackers raped his wife and

stole cash and jewelry as well as Mr. Ngugi's laptop computer. One of the

intruders burned Mr. Ngugi's face repeatedly with a cigarette. So brazen was

the attack, some Kenyans have speculated it might have been carried out by

former enemies.

''Welcome to the new Kenya, sir,'' wrote Lucy Oriang, a columnist for The

Daily Nation, Kenya's main newspaper. ''In the old days, you struggled to

stay a step ahead of political terrorists-cum-state agents. These days, you

watch out for both political and criminal thugs.''

The attack on Mr. Ngugi, who remains hospitalized, tainted what had been

a joyful return to his homeland. Because the government had banned his work

from bookstores and schools, Mr. Ngugi's writing has been better-known

elsewhere in Africa than in Kenya. But from the moment he arrived at the

Nairobi airport on July 31, Mr. Ngugi, 66, has been swarmed by well-wishers.

Mr. Ngugi's politically charged writing documented Kenya's repressive

days and chronicled the country's difficult transition from colonialism to

self-rule. In 1977, he wrote ''Petals of Blood,'' which portrayed

post-colonial Kenya in a harsh light. Later that year, his play ''Ngaahika

Ndeenda'' (''I Will Marry When I Want''), written with Ngugi wa Mirii, was

performed in an open-air theater in Limuru. It dealt with the inequalities

and injustices of the time and prompted the government led by Kenya's first

president, Jomo Kenyatta, to demolish the theater and imprison Mr. Ngugi.

|

|

|

|

Behind bars, he used toilet paper to keep putting down words -- in Gikiyu,

the language of the Kikuyu, not English, the tongue of the colonialists. First

came ''Devil on the Cross,'' in which thieves compete to see which among them

can best rob from the people, and then ''Detained: A Writer's Prison Diary.''

When he finally won release, the government barred him from returning to his

teaching job at the University of Nairobi or from teaching at other educational

institutions. But it could not stop his pen.

In 1982, while promoting ''Devil on the Cross'' in London, he learned of

plans by President Daniel arap Moi to arrest him again, and he decided not to

return to Kenya.

From overseas, he continued to rile the men he contended were ruining his

beloved Kenya. His novel ''Matigari,'' published in 1986, led the government to

issue an arrest warrant for the fictional man in the book who was roaming the

countryside in search of justice. When officials could not track down the

character, Matigari, they banned the book.

Years ago, Mr. Ngugi vowed not to return to Kenya until Mr. Moi had left

office. That happened in December 2002 when Mr. Moi agreed to abide by term

limits, and his handpicked successor, Uhuru Kenyatta, lost the election. The

opposition united behind Mwai Kibaki, who won.

Mr. Kibaki's Kenya has made progress, but crime is still out of control, with

a huge rich-poor divided and a less than effective police force. Mr. Ngugi has

said, however, that the Kenya of today is not the same place he left. For one

thing, Kenyans no longer have to look over their shoulders for informers when

they talk politics.

''I have not sensed that fear,'' he told The East African Standard, a Nairobi

daily, in a recent interview.

All the same, Mr. Ngugi said African leaders need to be closer to their

people. ''As long as there is a divorce between the leadership and the people,

we are weak,'' he said in the interview. ''As long as there are divisions

between peoples, we are weak. And as long as there are divisions within Africa

-- African peoples and nations -- we are weak.''

Despite the awareness that Kenya still has a long way to go, Mr. Ngugi, who

now teaches writing at the University of California, Irvine, has had many happy

times during his stay.

He and his wife, Njeeri, knelt and kissed the Kenyan soil when they arrived.

He lectured at the University of Nairobi. Wherever he went, he spoke to ordinary

people, using his native language and feasting on their delicacies -- roasted

goat ribs, for instance, and irio, a mashed mixture of potatoes, corn and beans.

''I harbor no bitterness or desire for vengeance,'' he said on his arrival in

Kenya. ''In culture and politics, the only worthwhile vengeance is to strive for

positive change against the negative forces of yesterday.'' At a news conference

at the hospital on Sunday at which he was asked if he regretted returning, he

said, ''This is my country, for better or worse, and it's for me and everybody

else to make it a Kenya that it can be.''