Scroll down for article....

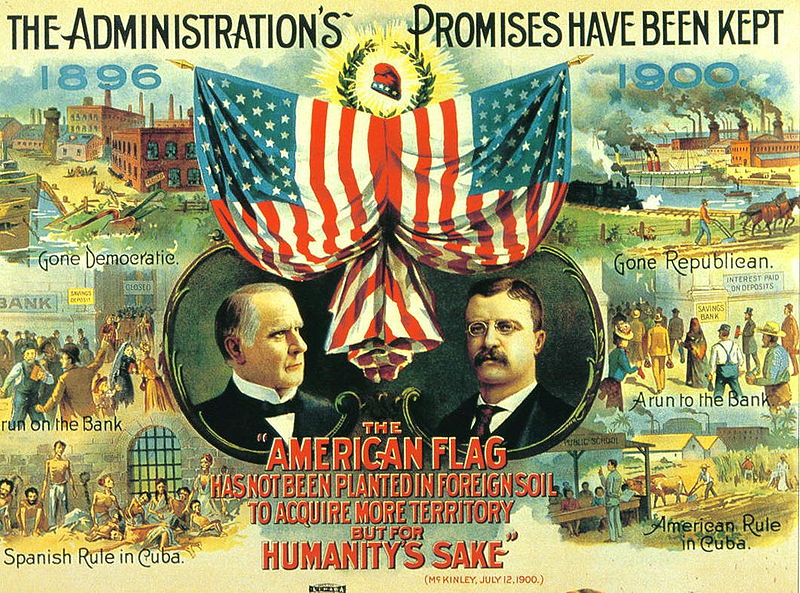

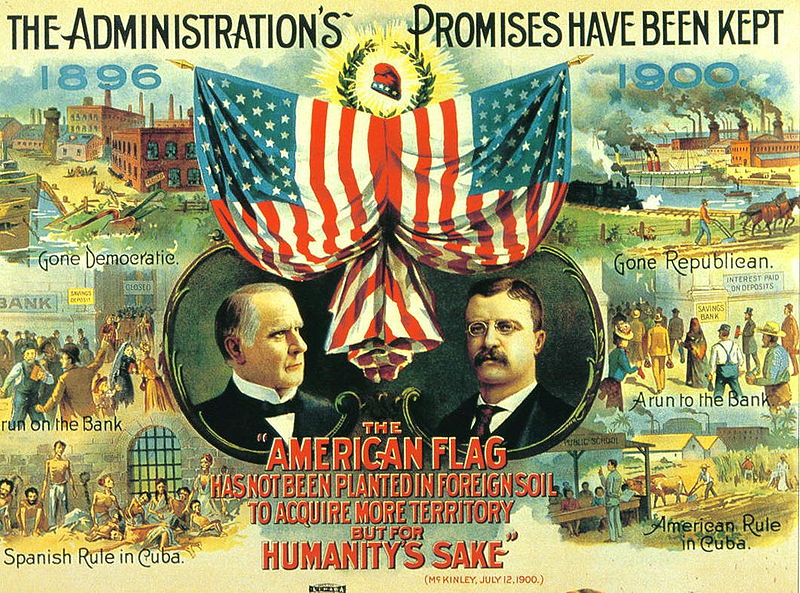

Bolivia is the only Cold War example I know where the U.S.from Eisenhower on worked with, rather than against, a leftist government with a revolutionary, populist agenda which included nationalization of business assets of U.S. companies. At about the same time (early 50's) the U.S. engineered the downfall of the governments of Iran and Guatemala for fear a Russian allegiance could form. Guatemala was a fife of United Fruit too close to home (like Cuba), and Iran was oil rich and bent on ousting British Petrolium, and was strategically important in terms of geography. Bolivia was different because it was very poor, dependant on the U.S. for aid, and the business interest at issue, tin mining, relied on U.S. markets. Also Bolivia did not flirt with the Soviets the way Guatemala did, by receiving a Soviet arms shipment. The U.S. did not see Bolivia as a threat to break away from the U.S. leash and go communist. It should be noted that President Truman was against a U.S. sponsored coup in Iran, and if Adlai Stevenson had become president in 1952, instead of Eisenhower, the world would probably have seen many more negotiations, as in Bolivia, where military coups were the Republican's chosen method. These were crucial elections for foreign policy, maybe: it is not clear how Stevenson would have behaved in the Cold War arena. Historically similar were the McKinley Bryan elections of 1996 and 1900. In 1900 McKinley traded in on the recent war of acquisition, the Spanish American War, which Spain was squirming to get out of before it started, so the U.S. blew up one of its own battleships in Cuba (The Main) as a pretext to declare war. For a Wikipedia treatment of this election and the surrounding issues, click here. Below is a 1900 Republican campaign poster. Note the same argument that the U.S. uses now in Iraq and Afghanistan and that it used during the Cold War: "The American flag has not been planted on foreign soil to acquire more territory but for humanity's sake." In fact more U.S. military died suppressing Aguinaldo and democracy in the Philippines after the war than died fighting the Spanish. Hawaii was stolen from the locals in a series of moves between 1893 and 1900. The 1900 election was not even close. Americans saw the Europeans grabbing colonial plots in the Pacific to lucrative ends, and they were sick of standing around not getting some too. In South and Central America, however, the U.S. had been manipulating and exploiting since the early 1800's. (Monroe Doctrine.)

|

|

|

Volume XV, Number 2, Fall 1995TABLE OF CONTENT |

To Intervene or Not To Intervene:

A Comparative Analysis of US Actions

Toward Guatemala and Bolivia in the Early 1950s

by Ingrid Flory and Alex Roberto Hybel

INTRODUCTION

Shortly after the end of the Second World War, the United States faced the task

of having to determine how to respond to foreign governments that did not

aggressively seek to curtail the actions of communists within their states. This

problem was not endemic to any one region, but it had a distinct significance in

Latin America. The US government became convinced that the “the domination or

control of the political institutions of any American State by the international

communist movement . . . would constitute a threat to the sovereignty and

political independence of American States."1

Guatemala and Bolivia were among the first two Latin American countries to force

Washington to address this problem. In the early part of the 1950s both

countries were governed by leaders who seemed willing to permit the active

participation of communists in their respective domestic systems. Moreover, both

countries initiated a variety of radical economic and social reforms, many of

which were in tune with policies implemented by the Soviet Union and the

People's Republic of China and had been demanded by the local, national

communist party. Despite these similarities, the US was of two minds in its

assessment of the nature of the problems posed by Guatemala and Bolivia.

Shortly after Dwight D. Eisenhower became president of the United States.

Secretary of State John Foster Dulles noted that international communism had

been probing for nesting places in the Americas, and that "[i]t finally chose

Guatemala as a spot which it could turn into an official base from which to

breed subversion which would extend to other American Republics."2 The

administration concluded that Guatemala had become a communist center because

its president '"had appointed communists to several strategic government

positions, permitted an increase in the volume of government propaganda,

supported labor leaders with communist affiliations, and conducted a foreign

policy parallel to that of the Soviet Union."3 Bolivia's president, on the other

hand, though initially tolerant of the communists, was believed to have finally

recognized "the fundamental rivalry between [his party] and the communists, and

ha[d] gradually adopted a more anti-Communist attitude. [He] ha[d] also

recognized that close association with the communists would diminish [his]

chances of getting US aid."4

Having defined the problems posed by Bolivia and Guatemala differently.

Washington, justifiably, came up with different solutions. On 6 July 1953, the

Department of State announced that the United States, in an attempt to help

Bolivia overcome its economic woes, would sign a "one-year contract for the

purchase of tin concentrates (at world market prices). ... double its

technological assistance program, and . . . consider additional measures to

assist Bolivia in the long-range solution of its problems."5 Less than a year

later, on 18 June 1954. President Eisenhower authorized the Central Intelligence

Agency to launch a covert paramilitary operation designed to topple the

Guatemalan government. Nine days after the operation had been authorized,

Guatemala's president, Jacobo Arbenz, resigned. He was succeeded ten days later

by the leader of the covert operation. Carlos Castillo Armas.6

What persuaded the Eisenhower administration that, although the governments of

Bolivia and Guatemala had initiated similar domestic policies and had for some

time worked closely with the communists, their actions justified different

responses? In order to explain Washington's presumed inconsistency one must

account for the Eisenhower administration's reliance on analogies to define and

respond to international problems and for the manner in which the targeted

states responded to such analogies. More specifically, the Eisenhower

administration was initially convinced that communists in the two Latin American

countries were relying on the same strategy their counterparts had employed in

China in the 1930s to gain power. However, the US took different actions toward

the two countries because Bolivia's leaders understood the significance of this

analogy and sought to persuade Washington that Bolivia would

not become a "second China," while Guatemala's leaders did not grasp the

significance of the China analogy and as a result did not try to convince

Washington that they were committed to preventing the rise of communism in their

country.

THE ROLE OF ANALOGIES IN THE FORMULATION OF FOREIGN POLICIES

The assumption that political leaders could be viewed as rational international

actors gained momentum shortly after the end of the Second World War. Decision

makers comprising the official, bureaucratic manifestation of the state were

assumed to act as a body with a single mind, capable of formulating foreign

policies based on rational calculations of the effect such policies would have

on the state's power. As noted by Hans Morgenthau, to give meaning to the raw

material of foreign policy, i.e., power, political reality had to be approached

with a rational outline.7

In the late 1960s and throughout the larger part of the 1970s, the study of

foreign policy experienced a critical metamorphosis. It was pointed out that

rational choice requires the gathering of vast amounts of information, the

generation of all possible alternatives, the assessment of the probabilities of

all consequences of each alternative, and the evaluation of each set of

consequences for all relevant goals. A new generation of scholars recognized

that fulfillment of these requirements were beyond the reach of most foreign

policy makers or, for that matter, of most human beings. As Herbert Simon noted,

these requirements are "powers of prescience and capacities for computation

resembling those we usually attribute to God."8 In addition, it was realized

that because on a typical day foreign policy makers address a wide array of

international problems, they allot different amounts of time to different

problems, depending on their significance and, as a result, examine some

problems more carefully than others.

During this period, another group of scholars proposed that rationality is

impeded not only by the absence of extraordinary intellectual powers and by the

shortness of time, but also by the decision maker's own beliefs and cognitive

conditions. Borrowing from theories of cognitive consistency, analysts

maintained that when a human processes and interprets information, that person

is not just attempting to understand a problem and formulate a solution; he/she

is also trying to ensure that as he/she conducts such tasks his/her beliefs and

cognitions about an object or concept and any external beliefs and cognitions

about the same object or concept remain consistent.9 When the external beliefs

and cognitions about an object or concept do not contradict those of the

decision maker, the relationship remains stable. If a contradiction exists and

leads to a conflict, then the decision maker must decide whether to alter

his/her perspective. This decision is in large measure a function of the

intensity of personal beliefs. The greater the intensity of those beliefs the

greater the likelihood that the decision maker will not modify his/her position.

Another cognitive theory that has been widely used by students of foreign

policy-making is schema theory. Schema theory suggests that the decision maker

attempts to shorten and simplify the decision-making process. The need for short

cuts may stem from sheer laziness, lack of time, or even shortage of

information. Schema theory's driving assumption is that decision makers reason

analogically.10 Analogies are schemas, or cognitive scripts, stored in memories

in the form of structured events that tell familiar stories. Cognitive scripts

are either episodic or categorical. The foreign policy maker infers an episodic

script by analyzing a single experience defined by a sequence of events. An

example of an episodic script is the "Yenan Way" script. The script, designed by

foreign policy makers in the Truman administration, was used to contend that the

radical agrarian reforms instituted in China in the 1930s were the prelude to

communist domination in that country. A categorical script is a generalization

of an episodic script. In the above example, the ''Yenan Way" script was used to

justify the generalization that radical agrarian reforms were a preamble to

communist regimes. A categorical script need not be the result of several past

experiences: one impressive incident can spur a decision maker to transform an

episodic script into a categorical form." The decision of which script to store

in memory and use is a function of the foreign policy maker's beliefs and

values. A foreign policy maker commits to memory only those scripts that are

politically, socially, economically, or morally important to him/her. This means

not only that the choice of scripts is subjective, but also that the content of

the scripts stored from any one experience can differ from one individual to

another.

Analysts have argued that a foreign policy maker uses the same cognitive script

to address similar problems until he/she encounters a situation in which the

employment of the same script results in costly consequences. This study agrees

with the postulate, but adds an important qualifier. According to Theodore

M. Newcomb, a decision maker's willingness to accept information or an analysis

from a second party is to a large extent a function of whether the source is

considered suitable. If the source is believed to be reliable, one of two

outcomes can ensue. When the decision maker and the source agree, their

relationship is termed "positively balanced." Under this condition, the decision

maker does not need to modify his/her stand. When the decision maker disagrees

with the source, the relationship is termed "positively imbalanced." Under this

condition the decision maker is forced into a trade-off situation. He or she

either has to sacrifice his/her own perspective and accept that of the source or

vice versa.12 Based on Newcomb's argument, this study intends to propose that a

foreign policy maker need not always experience costly consequences to abandon a

cognitive script. He/she is bound to make a similar decision if apprised of the

script's inapplicability by a trusted advisor or a reputable decision maker.

THE GENESIS OF TWO CHALLENGES

Eisenhower moved into the White House in early 1953, convinced that communism

posed the greatest threat to international stability and that the United States

had a moral obligation to use military, political and economic means to contain

it. "It is the rooted conviction of the present administration," he noted, "that

the Kremlin intends to dominate and control the entire world."13 Any attempt on

the part of the United States "to sit at home and ignore the rest of the world."

in the face of such a threat would lead to one consequence: "destruction."14

This attitude colored Eisenhower's perception of Latin America. After lamenting

during a National Security Council meeting that the United States, due to its

commitment to "raising standards of all peoples," was inhibited from assigning

"whatever proportion of national income" it so desired to warlike purposes, the

new president emphasized that in the case of Latin America his administration

would have to design policies to "secure the allegiance of these republics to

our camp in the cold war." Similar views were conveyed not long after by

Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, who noted that "the Communists are trying

to extend their form of despotism in the hemisphere" and that the challenge

would be to convince Latin Americans that communism was "an international

conspiracy, not an indigenous movement:'1"' Of great concern to Dulles was

Guatemala. "For several years international communism has been probing here and

there for nesting places in the Americas. It finally chose Guatemala as a spot

which it could turn into an official base from which to breed subversion which

would extend to other American Republics."16

Eisenhower and Dulles were not the first US leaders to be troubled by

developments in Guatemala. As the Second World War moved to a close, Washington

was forced to turn its eyes toward Guatemala. In 1944, after being ruled for

nearly thirteen years by Jorge Ubico, Guatemalans forced him to resign and

elected Jose Arevalo as their new president.

On 15 March 1945, at his inaugural speech, Arevalo announced that it was his

intention to free Guatemala from Washington's control. His new program, coined

"spiritual socialism." was predicated on the assumption that government had to

create the conditions that would facilitate the individual's psychological

development and moral liberation. The program disavowed both Marxism and

individualistic capitalism. According to Arevalo, by viewing the individual as

an economic animal and by prescribing class struggle, Marxism undermined the

individual's spiritual foundation. In turn, individualistic capitalism, with its

emphasis on the individual over collective interests, weakened the structure of

society.17

Washington took Arevalo's ascent to power seriously. Upon evaluating Guatemala's

new constitution, the State Department concluded that it was free of communist

dogma. The State Department later wrote that: "Like other recent constitutions

in Latin America and elsewhere, the Guatemala charter heavily emphasized the

responsibility of the state with respect to economic and social matters and

asserted its concern for the welfare of the underprivileged. It formulated

ambitious economic goals; it spelled out extensive social reforms; it called for

a more equitable distribution of the national income. It specifically provided

the basis for the emergence of a protected labor force and for land reform

legislation."18

To be free of communist dogma, however, did not signify that the Guatemalan

government was free of communist influence. Of great concern to Washington were

the policies the Arevalo administration had began to implement, and whether such

policies might be the result of communist influence. In 1945, the Arevalo

government expressed its support of the Caribbean Legion, a radical Latin

American organization committed to ousting dictatorships, by force if necessary.

Between 1946 and 1947, the new Guatemalan government instituted social security

and Labor Code laws that threatened United Fruit's investments in the

country.

These developments persuaded Washington that it needed a representative in

Guatemala who would speak bluntly about US concerns and interests. In 1948,

President Truman appointed Richard Patterson, an individual well-known for his

anti-communist sentiment and recent work in Yugoslavia, US ambassador to

Guatemala. Patterson did not waste any time in expressing his country's

discontent with the policies of the Arevalo government. At a dinner hosted in

his honor in January 1949, he warned the Guatemalan president that his job as

ambassador was to promote US interests in Guatemala and that the relations

between both countries would suffer if the host country did not stop persecuting

those interests. A year later, Ambassador Patterson went so far as to demand

that Arevalo dismiss seventeen government officials, all of whom were denounced

as being communists.

By 1950, the Truman administration had concluded that the communists in

Guatemala were taking advantage of the country's free processes and institutions

to expand their own power and to destroy freedom. Washington, however, was still

unwilling to take a major stand against the Arevalo government. The Truman

administration caved in when the Arevalo government demanded that Patterson be

removed from his post following his demand that Guatemalan officials be

dismissed. This action did not reflect an absence of commitment on the part of

the Truman administration to stop the growth of communism in Guatemala. Instead,

it reflected the hope by some State Department officials that Guatemala, under

the leadership of a newly elected president, would be more responsive to US

concerns.

Jacobo Arbenz Guzman was sworn in as Guatemala's new president in March 1951.

Perceptions about Arbenz prior to his inauguration varied. Edward Miller, the

assistant secretary of state for inter-American affairs, and Milton Wells, the

first secretary at the US Embassy in Guatemala, believed that Arbenz, because of

his military background, would change Guatemala's pro-Soviet course and veer

toward the center. State Department official Tapley Bennett and Ambassador

Patterson, on the other hand, were convinced that the Soviet Union had approved

Arbenz's candidacy, that all communist-controlled organizations in Guatemala

supported him, and that the new president was committed to following a communist

policy.

These differences became inconsequential by the middle of 1952. Thomas Mann, who

as deputy secretary of state for inter-American affairs had led the US

delegation to Arbenz's presidential inauguration, returned from the trip

convinced that the Soviets had finally succeeded in placing a communist in

power.19 His argument was bolstered by the Guatemala Labor Court's January 1952

order that the American-owned United Fruit Company re-hire 4,500 Guatemalan

employees who had been laid off for three years and pay them $650,000 in back

wages, and by the fact that five months later the Arbenz administration

instituted an agrarian reform bill that called for the division and

redistribution of idle land exceeding 223 acres, including land owned by foreign

corporations.20

Impressed by Thomas Mann's argument and convinced that the radical reforms

implemented in Guatemala substantiated Mann's analysis, Truman briefly

considered launching a covert paramilitary invasion to overthrow Arbenz. On the

advice of Secretary of State Dean Acheson, however, Truman decided against such

a measure for fear that an invasion would undermine the reputation of the United

States in Latin America.21 Truman also did not believe that the plan could be

completed and implemented before the end of his term. These concerns were

anticipated by Arbenz, who in September 1952 paid a visit to the US ambassador

to Guatemala. Rudolf C. Schoenfeld, and asked whether the United States regarded

the Guatemalan government as communist. Schoenfeld responded that the US

government "saw Communists holding key positions in various agencies and

institutions and many evidences of Communist activity . . . [and] that this

denoted a serious degree of Communist infiltration in the country and a

tolerance for it. . ."'— Schoenfeld later noted that Arbenz had been interested

and attentive at their meeting, but that "he gave no hint that he planned to

take any action" to limit the activities of the communists.23

A few months after Truman had aborted the covert paramilitary plan, a new

administration arrived in Washington. The Eisenhower administration's first

action toward Guatemala occurred mid-1953, when the Department of State

submitted a formal complaint to the Arbenz regime concerning the nationalization

of property owned by the United Fruit Company. Subsequently, the president

ordered the Department of State to draw a plan designed to control Soviet

expansion in Central America. According to the plan, the United

States would form a coalition with the nations surrounding Guatemala for the

purpose of mounting political and economic pressure on its government, forcing

Arbenz either to resign or to expel the communists.24 The coalition would also

protect surrounding nations from communist infiltration from Guatemala.

Determined to gain a better perspective on the communist threat in Latin

America, President Eisenhower asked his brother Milton to visit the region. Upon

his return in July 1953, the president's brother reported that Guatemala had

"succumbed to communist infiltration.”25 Milton Eisenhower's report,

substantiated by the continued redistribution of land owned by the United Fruit

Company, motivated Eisenhower to order the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to

prepare a plan designed to covertly overthrow the Guatemalan government.26

For the next year, Washington kept to a minimum its interaction with the Arbenz

government. Aware that relations were not good between Guatemala and Washington,

the Arbenz regime sought to persuade the US representatives that "the Communist

issue [was] a false one fabricated by the United Fruit Company”'27 In February

1954, the Guatemalan president proposed the appointment of a neutral commission

to arbitrate Guatemala's dispute with the company. Washington rejected the

offer, and when two months later the Arbenz administration offered United Fruit

SI. 185.000 in compensation, the US government countered with a demand for

$15.854,849.28 At about this time, the Arbenz government intercepted a letter

from a Castillo Armas, a Guatemalan national, to Anastasio Somoza, Nicaragua's

ruler, stating that Washington had finally decided to overthrow the Guatemalan

government.29 In hopes of protecting his regime from this threat. Arbenz asked

the United States to lift its arms embargo on Guatemala.311 Washington refused,

and pressured its European allies not to accept any requests for arms by

Guatemala. With nowhere else to go, Arbenz turned to the Soviet bloc.

Arbenz's decision unwittingly afforded the United States a major point of

leverage. In mid-May 1954, 2.000 tons of Czechoslovakian arms arrived in

Guatemala. After learning about the arrival of the weapons, Eisenhower

authorized the CIA to put into action its plan to overthrow the Arbenz

government. Aware that his presidency was in jeopardy, Arbenz requested a

meeting with Eisenhower. The US Ambassador to Guatemala, John Peurifoy, whose

principal task was to help coordinate the paramilitary attack on the Arbenz

government, declined the meeting and emphasized that the United States was not

concerned about the fate of the United Fruit Company but of communism in

Guatemala. Peurifoy's remarks were upheld by Secretary of State Dulles on 8 and

10 June when he emphasized that even if the United Fruit matter were settled,

the presence of communism in Guatemala would still remain a problem.31 On 18

June 1954. Castillo Armas and a small number of paramilitary forces, financed

and trained by the CIA, entered Guatemala. Upon realizing that Guatemala's armed

forces would not defend his government, Arbenz resigned.

Guatemala was not the only Latin American country that forced Washington to

carry out major policy changes. Less than a year before General Eisenhower

assumed the presidency, the Movimiento National Revolucionario (MNR), became

Bolivia's new ruling party. The ascension to power of the MNR was not well

received in Washington. The Truman administration, fearing that the MNR would

not respect international agreements and private property and would open the

doors to communism, waited seven weeks before granting the new Bolivian

government formal diplomatic recognition. And yet, about a year after the MNR

had assumed power, the Eisenhower administration announced that the United

States would buy Bolivian tin ores at the world market price (at the time of

delivery) for one year, would double the amount of technical assistance to

Bolivia, and would assist Bolivia to resolve some of its other economic

problems.32 These steps reflected a dramatic change in Washington's behavior

toward the MNR. The MNR was formed in 1941, six years after the Chaco War

between Bolivia and Paraguay had come to an end. The Chaco War, one which

Bolivia was supposed to win, but did not, "provided the stimulus which

eventually would give rise to a new political order in Bolivia."33 On the eve of

the Chaco War. Bolivia was a highly stratified and under-developed state.

Although its mining industry had grown considerably and there had been some

increase in urbanization, most of the population still depended on traditional

subsistence agricultural crops. In fact, even when compared with the experiences

of the people in other Latin American countries, the majority of Bolivians

"lived a harsh and brutal life."34

Dissatisfied with the structure of the Bolivian political, economic and social

system, and convinced that their senior military officers were incapable of

leading, a coalition of junior officers, led by Colonel David Toro and

Lieutenant Colonel German Busch, launched a bloodless coup in May 1936. Shortly

after

assuming power. Colonel Toro announced that the new military government had no

intention of implanting caudillismo. Its objective, he added, was "to implant

state socialism with the aid of the parties of the left."33 One of the initial

steps taken by the regime was to establish for the first time a minister of

labor. This action was followed almost immediately by the expropriation of the

petroleum concessions controlled by the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey and

by the establishment of the State Socialist Party, which was to act as the

political expression of the new regime.

The Toro regime was overthrown in July 1937, by Lieutenant Colonel Busch. The

new Bolivian leader immediately began to implement policies more radical than

those approved by his predecessor. He established the country's first labor

code, nationalized both the Central Bank and the Mining Bank, and issued a

decree requiring that all mining companies sell all the foreign exchange they

earned by selling their products abroad to the Central Bank.36 The decree was

supported by the vast majority, but opposed by the major mining companies.

In August 1939, Busch, who had been ruling the country as a dictator for nearly

five months, committed suicide. He was immediately replaced by General Carlos

Quintanilla, whose first act was to cancel the decree pertaining the sale of

foreign exchange. Quintanilla, and his successor, General Enrique Penaranda,

sought to put a stop to the economic changes that had been ensuing since the end

of the Chaco War, but their attempts were unsuccessful.

Probably the strongest reminder that the clock could no longer be turned back

was the formation of new: political parties committed to challenging the status

quo. These parties covered the entire ideological spectrum. At the far right

stood the Falange Socialista Boliviano, a party made up of intellectuals with

some contacts among military officers and patterned after the Spanish Falange

party. At the far left stood two parties, the Partido Obrero Revolucionario

(POR) and the Partido de Izquierda Revolucionario (PIR). The POR had Trotskyist

inclinations, while the PIR represented the Stalinist trend. The most important

party to appear during this period, however, was the MNR.37 The MKR, which

counted among its founders Victor Paz Estenssoro, the head of the Mining Bank

under the Busch regime, agreed with the PIR and POR on at least two issues. It

acknowledged the need to nationalize some of Bolivia's major means of production

and support the nascent labor movement. Its uniqueness, at least during the

early stages, was reflected by its position regarding the Indian problem and

international affairs. In the 1940s, Bolivian Indians were still experiencing

discrimination. Both the POR and PIR demanded an end to this unjust treatment,

but the MNR, possibly due to its middle-class origin, did not voice its

preference. On matters of international affairs, the MNR had no qualms about

expressing its opinion. Although it contained a variety of factions from former

Nazis to Marxists, during the early stages of the Second World War it expressed

a pro-fascist position. This stand was at odds with the PIR which vigorously

argued that it was in Bolivia's national interest to support the Allied cause.38

These new parties remained in the background during the early years of the

1940s. President Penaranda succeeded at hindering the drive for change until

late 1942, largely because his supporters controlled the Bolivian Congress.

During this period he also managed to assure Washington that it would continue

to have access to Bolivian tin as the United States became more entangled in the

new world war. Bolivia's domestic and international panorama began to change in

late 1942. In December of that year, miners struck against the Catavi mine.

During one of the demonstrations, troops opened fire killing a substantial

number of participants and wounding others. The MNR used the incident to

strengthen its relations with the miners. At the same time, fearful that the

incident could lead to further disruptions, thus undermining Bolivia's ability

to maximize its production of tin, the US government dispatched a mission to

look into labor conditions at the tin mines. Members of the mission submitted a

report recommending that the Bolivian government improve the working conditions

at the mining camps.39

The Penaranda regime managed to remain in power for one more year. It was

finally ousted in December 1943, by a group of young military officers and the

MNR. The United States took very little time to express its opposition to the

new government. Washington feared that Argentina, which had just had its own

military coup six months earlier and had openly expressed its pro-Axis stand

might have helped instigate the Bolivian overthrow.40 Furthermore, the US

government did not trust the MNR. Washington's uneasiness originated in 1940,

when Britain, in an attempt to induce support from the United States and Latin

America against Germany, fabricated a letter to both the United States and

Bolivia stating that a Nazi "putsch" was

developing in Bolivia. Upon the arrival of the letter, the Bolivian government

expelled Germany's minister, declared a state of siege, and arrested several

political leaders, including members of the MNR. In turn, the US drew a link

between the MNR and Nazi-Fascism. It did not try to suppress the MNR leaders or

label them Nazi, but because of the party's earlier and continuing opposition to

the Standard Oil settlement and the government's action, it "thereafter

associated them with Nazi-Fascism.”41

This perception had a major effect on Washington's actions following the 1943

coup. Upon assuming power, the new Bolivian president, Major Gualberto

Villarroel, appointed three members of the MNR to his cabinet. US Secretary of

State Cordell Hull, convinced that the hemisphere was "under sinister and

subversive attack by the Axis, assisted by some elements within the hemisphere

itself," ordered the Department of State to warn Bolivian officials that the

United Stated would not recognize their new government unless the three MNR

members were removed from the cabinet. Villarroel acceded, and the United States

recognized his government in June 1944.42

Recognition of the new government did not foster better relations between the

two countries. From the moment Villarroel assumed power to the day he was

assassinated in July 1946, the United States intervened in Bolivia's domestic

affairs by taking positions which coincided with those of the owners of the tin

mines and against the Bolivian government. The Villarroel government, cognizant

that its battles with the tin mine owners were being undermined by the United

States, repeatedly pleaded with Washington to behave impartially, but to no

avail.43

With Villarroel dead and a government friendly to the tin mine owners in power,

the US government assumed that Bolivia might finally become a country responsive

to the interests of the United States. As noted by US Ambassador to Bolivia

Joseph Flack in a telegram to Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American

Affairs Spruille Braden: "A popular revolution in every sense of the word has

just occurred in Bolivia . . . this may prove first democratic government in

Bolivian history. Immediate prospects are greatly improved relations with the

United States . . .”44 Flack's prediction proved to be erroneous.

Although the new Bolivian government managed to remain in power until 1951, it

did not placate domestic discontent. Bolivia's dependence on foreign markets for

the sale of tin, and the fact that tin magnates resided abroad and that profits

flowed from the country to them, convinced Bolivians that their ills were caused

by external forces. Thus, when faced in 1951 with chronic economic crises

brought about by the decrease in the foreign demand for tin. Bolivians vented

their anger with the ruling party by electing as their new president the leader

of the MNR, Victor Paz Estenssoro. However, the military did not accept Paz

Estenssoro's victory, and on 16 May 1951, it established a new junta under the

leadership General Hugo Balliavian. The junta announced that it was annulling

the elections because the MNR was in league with the communists.45 The junta,

however, soon realized that it would not be able to placate the masses. On 9

April 1952, General Antonio Seleme, the head of the Carabineros, extended his

support to the MNR. The MNR immediately distributed arms to civilians and

workers and with the support of the Carabineros marched against the military.

After three days of fighting the military surrendered, and the MNR asked Paz

Estenssoro to return from exile to head the new government.46

This development was not well received by American foreign policy makers. They

feared that a regime that was led by the same individuals who had been tagged as

Nazis during the Second World War, that was backed by the communists, that was

very critical of US foreign policy, and that called for the nationalization of

the tin mines, could pose a threat to American interests in the region.

Washington displayed its concern by waiting until 2 June to grant formal

diplomatic recognition to the new government.

Recognition did not intimate that Washington was less apprehensive about Bolivia

being governed by the MNR. In fact, on 8 September, Secretary of State Dean

Acheson sent a telegram to the United States embassy in Bolivia advising the

Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC), which managed the US strategic

stockpile of tin, not to sign "long term tin contract so long as uncertainty

exists regarding nationalization of mines. Department's position has been based

on fear that signing long term contract could be considered by Bolivian

government as green light to confiscatory nationalization and that this would

have bad effect in other countries where U.S. property rights are at stake."47

This type of response from Washington did not stop the Paz Estenssoro regime

from pursuing its own political and economic agenda. One of the first steps

taken by the new government was to pass an electoral

law that extended the franchise to the Indian peasantry. Furthermore, in an

attempt to reduce the chance of a counter military coup, the MNR dissolved the

country's armed forces and chose, instead, to depend on the support of the

Carabineros and the armed militia of the workers and peasant unions.48

The major reforms initiated by the Paz Estenssoro regime, however, were in the

economic arena. First, in October 1952, it nationalized the tin mines belonging

to the three large tin mining companies, Patino, Aramayo and Hochschild. The

newly nationalized mining industry came under the jurisdiction of the

Corporacion Minera de Bolivia. Its second economic step was to initiate a major

redistribution of the country's landholdings. This end was to be accomplished by

drafting a new agrarian reform law, organizing the peasants and expanding

markedly the social services extended to the peasants. On 2 August 1953,

President Paz Estenssoro signed the new agrarian reform law, which transferred

massive amounts of rural property from the white or near-white traditional

landowners to the Indian peasants. The third step entailed the launching of a

major economic development program. The program was designed to expand the oil

industry, create new roads, and open the eastern part of the country.49

The policies initiated by the Paz Estenssoro regime easily could have alienated

the United States. To begin with, the US seldom welcomed nationalization,

particularly of companies that affected directly or indirectly its strategic and

economic interests. Moreover, Washington was very suspicious of the ideological

rationale behind agrarian reforms designed to bring about a more equitable and

just distribution of property. And yet, in 1953, the US, under the leadership of

an avowed anti-communist president, not only expressed trust in Paz Estenssoro,

but believed that his government understood that it would be imprudent to

maintain a close association with the communists. It was this belief that led

President Eisenhower to write President Paz Estenssoro on 14 October that the

"'friendly spirit of cooperation between our two nations . . . allowed him to

grant Bolivia with five million dollars in Commodity Credit Corporation stocks

of agricultural products to satisfy food needs of Bolivia, as well as four

million dollars in Mutual Security Aid funds for other essential commodities and

services . . ."50

THE RATIONALIZATION OF ANTITHETICAL POLICIES

The Eisenhower administration's perceptions of the situation in Guatemala were

not the result of a systematic analysis of communist activities in the country.

As Secretary of State Dulles noted on 11 May 1954, it would be "impossible to

produce evidence clearly tying the Guatemalan government to Moscow . . . the

decision must be a political one based on the deep conviction that such a tie

must exist."51 In the early 1950's, American decision makers were profoundly

influenced by their interpretations of developments in China prior to and after

Mao Zedong's communist party became the country's sole political force. In a

book titled The Yenan Way published in 1951, Eudocio Racines describes the way

the Chinese communists allied themselves with middle-class politicians and

ambitious army officers and worked themselves into positions of power in local

communities. The results of these steps, notes Racines, "were the Labor Code,

agrarian reform, and eventually strict censorship."52

American policy makers soon began to apply Racines' analysis to the situation in

Guatemala. Raymond G. Leddy, the Department of State officer responsible for

Central American and Panamanian affairs, testified before the House of

Representatives hearing on communist aggression that the "Guatemalan Way"

represented an improvement over the "Yenan Way" for the communists because it

taught them ways to deal with the situation in Central America more

effectively."13 Leddy's definition of the Guatemalan problem was not unique. US

Ambassador John Peurifoy, upon his arrival at his new post, warned Guatemala's

foreign minister that the parallels between the Guatemalan problem and the

Chinese problem had portentous implications. "Agrarian reform has been

instituted in China . . . and . . . today China is a communist country."34 A

similar argument was made by Secretary of State Dulles during his Senate

confirmation hearing. "[C]onditions in Latin America are somewhat comparable to

conditions as they were in China in the mid-thirties when the Communist movement

was getting started . . . The time to deal with this rising in South America is

now."35 But if the best time to deal with the rise of communism in a South

American country was when the movement was getting started, then what convinced

the Eisenhower administration that the "Yenan Way" analogy did not apply to

Bolivia?

One of the primary tasks of any foreign policy maker is to give meaning to

imprecise information. Rarely will a foreign policy maker attempt to carry out

this task without the advice of others. In other

words, who foreign policy makers speak with and listen to have a critical effect

on the analogy they rely on to define a problem.36 In 1953, the Eisenhower

administration was willing to consider soberly the arguments forwarded by

Bolivian officials but not by Guatemalan officials. Bolivian officials

understood that Washington would seriously question a Latin American

government's stance toward the United States, unless this government

acknowledged the reality of the communist threat and expressed an absolute

commitment to its obliteration. Guatemala did not grasp these simple, but

pivotal, facts.

Guatemalan leaders did not ignore Washington's unhappiness. Their mistake was to

assume that the US was concerned only with protecting the United Fruit Company,

and to take lightly its warning that the communist threat in Guatemala was real.

In September 1952, for instance, during the meeting between then US Ambassador

Schoenfeld and President Arbenz, the ambassador explained that Americans

believed that the "'Communists were unduly influential. They saw Communists

holding key positions in various agencies and institutions and many evidences of

Communist activity . . ." Schoenfeld added that, ''President Arbenz smilingly

assented but expressed doubt as to the accuracy of the estimates in Guatemala

... President Arbenz was patently interested and attentive but gave no hint that

he planned to take any action."07 Less than a year later, but now under the

Eisenhower administration, the Bureau of Inter-American Affairs at the

Department of State wrote: "We have frankly discussed the Communist problem with

high officials in Washington and in Guatemala. They have brushed aside our views

on Communist influence in the country as exaggerated. They have described the

Communist issue as a false one fabricated by the United Fruit Company."58

Probably the most telling example of the inability of the two governments to

understand one another came during a farewell meeting between Guatemala's

Ambassador to the United States, Guillermo Toriello, and President Eisenhower.

Ambassador Toriello, who was returning to Guatemala to become its new foreign

minister, tried before departing to convince Eisenhower that Guatemala's

problems were the result of United Fruit's economic policies and not of

communist activities, but to no avail. As Toriello sought to emphasize that the

"real question was not of communists in the Guatemalan Government, but of the

monopolistic position of the United Fruit in the country," Eisenhower kept

remarking that the United States "couldn't cooperate with a Government which

openly favored communists."39

In mid-May 1954, the Arbenz regime unwittingly afforded Washington the

opportunity to claim that its concern regarding the nature of the Guatemalan

government was fully justified. The US Embassy in Guatemala disclosed the

arrival of a ship transporting some 2,000 tons of Czechoslovakian small arms and

light artillery pieces. The purchase of these weapons had been the direct result

of the unwillingness by the Eisenhower administration to lift its arms embargo

on Guatemala, which had been in place since the early 1940s. In response to the

embargo, and concerned that his military would not be able to withstand a

CIA-backed paramilitary invasion, Arbenz solicited assistance from the Soviet

Union.60

Reaction by the Eisenhower administration was swift. Knowing full well that the

American Congress and public would be outraged if they learned that Guatemala

had just purchased weapons from a Soviet ally, it reported the transaction to

the American media. Congressional leaders called the weapons shipment "part of

the master plan of World Communism," and asserted that the weapons would be

"used to sabotage the Panama Canal."61 In turn. Secretary of State Dulles, in a

secret cable to various diplomatic offices, noted that: "A Soviet thrust into

Western Hemisphere by establishing and maintaining Communist-controlled state

between US and Canal Zone would represent [a] serious setback to [the] free

world. It would represent [a] challenge to Hemispheric-security and peace as

Guatemala has become increasingly instrumental of Soviet aggression in this

hemisphere.”62

Bolivia did not make Guatemala's mistakes. During the Second World War, the MNR

had learned painfully that a Bolivian government could not rule without the full

backing of the United States. More specifically, it learned that although the US

was committed to protecting its economic interests in Bolivia, it was also

willing to reach a balanced compromise so long as Bolivia demonstrated its

unbending opposition to the Axis powers. The chief problem during the first half

of the 1940s had been that President Villarroel had not persuaded the Americans

that appointing to cabinet posts a few MNR leaders did not indicate that his

government would side with the Axis powers instead of the Allies.63 For this

reason, the US government remained convinced until the end of the war that the

MNR was anti-Semitic, hostile to the Allies, and well-disposed toward the Axis

powers.64

None of this was forgotten by Paz Estenssoro and his new ambassador to the

United States, Victor Andrade.65 As Paz Estenssoro assumed the presidency in

1952, he remembered too well that he had been forced to resign in 1944 because

the US believed that his party, the MNR, was an ally of the Axis powers. This

time he was determined to ensure that Washington would not view him and his

party as puppets of the Soviet Union. At his inauguration speech he stated:

"[T]his is not an anti-capitalist government precisely because of the

seriousness of our task, which is in no sense demagogic. We want to ensure

progress for the majority: we take on this task and assume responsibility for it

because Bolivia is extraordinarily rich but it needs capital.''66 Paz Estenssoro

sought to reinforce the message already conveyed by Hernan Siles Suazo, who had

been sworn in as provisional president immediately after the MNR and the

Carabineros had defeated the Bolivian military. In his speech, Siles Suazo

emphasized that the new government was completely democratic "supported by the

great majority of the Bolivian people, with no relations to foreign parties,

least of all the Communist Party . . .”67

To reduce the likelihood that the United States would misread his government's

intentions, Paz Estenssoro appointed Victor Andrade as Bolivia's ambassador to

the United States. Few foreign diplomats understood the US Department of States'

thinking and decision-making process as well as Andrade. Andrade had served as

Bolivia's ambassador to the United States during the Villarroel government. His

principal task during that period was to convince the US to accept his

government's proposal to tax the tin mines on production rather than on profits,

and to control the percentage of foreign exchange from the tin sales the mine

owners would be permitted to keep.6R The US government yielded to Andrade's

argument, but too late. By the time Bolivia and the United States reached an

agreement. Villarroel was no longer in power. However, Andrade's experience

proved valuable. The Bolivian ambassador learned his way in Washington,

established important contacts, and by the early 1950s was working for the

Rockefeller's International Basis Economic Corporation in Guayaquil, Ecuador.69

From the moment Andrade was reappointed as Bolivia's ambassador to Washington in

1952, he made it clear that for the new MNR government to effectively implement

its domestic programs it would have to allay Washington's fears. "[T]he panorama

which confronted us," he wrote, "could be described in the following way: the

State Department was mistrustful of a regime which had been accused six years

earlier of collaboration with German Nazism and which now seemed to have

acquired contacts with international communism.”70 Andrade also believed that to

succeed he would have to help the US leaders understand Bolivia's

nationalization of the tin mines and land reform program. He emphasized that

nationalization of the tin mines was something that his government truly

regretted but that it had become necessary because the "three giants of mining

had usurped the nation's right to rule." He then added that his government did

not "relish the bad reaction which nationalization ha[d] caused in some quarters

of the United States . . ." and hoped that the "billions of dollars in the

United States that [sought] profitable outlets" would go to Bolivia where the

government was attempting to "create an atmosphere which attracts private

capital."71 Regarding Bolivia's land reform program. Andrade believed that

although "the reform did not directly affect U.S. interests, most American

leaders were suspicious because they knew nothing of the agrarian system which

prevailed in Bolivia up to the moment. Under the influence of reactionary

propaganda, these leaders were inclined to oppose the reform, believing that it

violated the democratic principles of the hemisphere."72

Andrade relied extensively on personal diplomacy and on his status as a

Washington insider to try to bring about a change in attitude towards the new

Bolivian government. His status as an insider was reflected by the fact that he

was one of the very few ambassadors who played golf with Eisenhower from time to

time at the Burning Tree Golf Club.'3 Andrade's closest Washington ally,

however, may have been the president's brother, Milton Eisenhower. It was at a

family party in Washington that Andrade proposed to Milton Eisenhower a visit to

Latin America "in order to study at first hand the delicate issues involved in

[Bolivia's] relations with the United States and the possibilities of mutual

cooperation."74

Milton Eisenhower's trip to Latin America proved to be the turning point in

US-Bolivian relations. His travel reaffirmed the Department of State's belief

that the MNR had to be viewed differently.75 More importantly, he brought back

from Latin America a new perspective. Upon his return he emphasized that it was

harmful to tag governments or political parties as communist "in good faith but

without essential knowledge." He added that the United States should "not

confuse each move in Latin America toward socialization with Marxism, land

reform with Communism, or even anti-yankeeism with pro-Sovietism."

Regarding the Estenssoro government, he noted that it "may have been

inexperienced, sometimes critical of us, and more inclined toward socialism than

Americans generally prefer . . . But [its leaders] were not Communists." He

concluded by pointing out that the only way to avert a revolution that would

bring the communists to power in Bolivia would be to support the rapid social

change being advocated by the Paz Estenssoro government.76

Milton Eisenhower's message did not fall on deaf ears. Following his trip to

Latin America, intelligence analysts and foreign policy makers alike argued that

the MNR had to be supported in order to contain communism in Bolivia. On 2

September 1953, Secretary of State Dulles wrote:

a situation dangerous to the security of the United States is developing in

Bolivia, and urgent action is required to meet it. Because of a sharp drop in

the price of Bolivia's principal export commodity, tin, owing to the imminent

cessation of United States tin stockpiling, Bolivia faces economic chaos. Apart

from humanitarian considerations the United States cannot afford to take either

of the two risks inherent in such a development: (a) the danger that Bolivia

would become the focus of Communist infection in South America, and (b) the

threat to the United States position in the Western Hemisphere which would be

posed by the spectacle of United States indifference to the fate of another

member of the inter-American community.7'

A month later, President Eisenhower authorized an emergency assistance program

that included: $5 million of agricultural products from Commodity Credit

Corporation Stocks under the Famine Relief Act; $4 million from Mutual Security

Act funds for other essential commodities; and a doubling of the technical

assistance program.78 The strategic significance of the emergency assistance

program was made more explicit a few weeks later by Assistant Secretary of State

for Inter-American Affairs John Moors Cabot, who applauded the MNR government's

opposition to "Communist imperialism" and the willingness on the part of the

United States "to sink our differences and to cooperate with regimes pursuing a

different course from ours to achieve common goals."79

CONCLUSION

President Eisenhower arrived in Washington determined to prevent the spread of

communism throughout Latin America. His commitment was based more on belief than

on factual information. The president and his advisers did not have the

information necessary to postulate a persuasive argument that communism in Latin

America was becoming a serious threat. But they did not need such information.

For them, a government's willingness to have a few communists in its cabinet,

maintain relationships with communist labor leaders, nationalize foreign

companies, and implement agricultural reforms, along with its unwillingness to

recognize that the communists were becoming a noteworthy force, meant that such

a government risked being usurped by communists. The communist takeover of

China's government in 1949, convinced the Eisenhower administration that these

developments could not be taken lightly. More specifically, it persuaded the

Eisenhower administration that these actions exhibited Moscow's determination to

install a communist regime and that if Washington hoped to thwart such an

attempt it would have to move swiftly.

The Eisenhower administration relied on the China analogy to characterize the

nature of the problem encountered by the United States in Guatemala under Jacobo

Arbenz and in Bolivia under Victor Paz Estenssoro. The new administration

believed that both Latin American leaders had been backed by the communists

under the agreement that when in power they would work together to alter the

economic and social structures of their respective countries. Washington was

uncomfortable with the arrangement, but was willing to tolerate it so long as

the Latin American leaders understood that when they assumed the presidency they

would have to break the agreement with the communists and move against them. An

unwillingness on the part of the Latin American leaders to acknowledge the

threat posed by the communists, and to act against them, was interpreted by the

Eisenhower administration to mean either that the government was dominated by

communists or that it was soft on communism. Either case left Washington with

one option: to try to topple the Latin American government before the communists

took over.

Any Latin American government that failed to comprehend Washington's strong

attachment to the China analogy risked being deposed. In Bolivia, Paz Estenssoro

understood this simple fact; in Guatemala. Arbenz did not. Paz Estenssoro and

Andrade well remembered the effect that Washington's belief that Bolivia

was being ruled by leaders who were pro-Axis had on the Villarroel government's

ability to rule in the mid-1940s. Both Bolivian leaders were determined not to

make the same mistake twice. From the moment they regained power, they went out

of their way to ensure that the Eisenhower administration would not perceive the

new Bolivian government as being either dependent on the communists or soft on

communism. The Arbenz government, on the other hand, without an insider in

Washington and the benefit of a costly experience, did not take seriously

Washington's warning that Guatemala was being threatened by the communists. And

for this error, it paid dearly.

Foreign policy makers are prisoners of the past. Their decisions are anchored to

lessons inferred from previous occurrences. To say that they are captives of

past events is not to assert that they cannot break the chain that ties them.

Although cracking the chain is not easy, particularly if the analogy came into

being as the result of a costly experience, it may be, in some instances, the

only way to avoid conflict. The avoidance of conflict demands an understanding

of how the party contemplating the use of force reasons. It also demands an

understanding of the analogy that dominates the would-be aggressor's thinking

process, a willingness to take the analogy seriously, and a determination to

prove that the analogy is inapplicable to the situation at hand.

Endnotes

Different versions of this paper were presented at the Annual Meeting of the

International Studies Association in Acapulco. Mexico, in March 1993: and at the

Annual Meeting of the New England Political Science Association in Northampton.

Massachusetts, in April 1993. We are grateful to the various commentators and

participants for their helpful suggestions. We would also like to thank the

three anonymous referees for their comments.

1. Declaration by the United States at the Inter-American Conference held in

Caracas. Venezuela, in 1954. Quoted in Philip B. Taylor. Jr., "The Guatemalan

Affair: A Critique of United States Foreign Policy,” The American Political

Science Review, 50, no. 3 (September 1956), p. 790.

2. Quoted in Robert Branyon and Lawrence H. Larson. The Eisenhower

Administration 1953-1961. A Documentary History (New York: Random House, 1971),

p. 311.

3. Alex Roberto Hybel. How Leaders Reason. U.S. Intervention in the Caribbean

Basin and Latin America (Cambridge, UK: Basil Blackwell, 1990), pp. 57-58. See

also Richard Immerman. The CIA in Guatemala. The Foreign Policy of Intervention

(Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1982), pp. 108, 119-20.

4. "National Intelligence Estimates." 19 March 1954, Foreign Relations of the

United States 1952-1954. The American Republics, Vol. TV (Washington. DC: US

Government Printing Office. 1983). p. 551. Cited hereafter as FRUS.

5. Earl G. Sanders, "The Quiet Experiment in American Diplomacy: An Interpretive

Essay on United States Aid to the Bolivian Revolution," The Americas, 33 (July

1976), p. 36.

6. See Hybel, How Leaders Reason: and Immerman. CIA in Guatemala. See also

Stephen Schlesinger and Stephen Kinzer, Bitter Fruit: The Untold Story of the

American Coup in Guatemala (Garden City, NY: Doubleday. 1983).

7. Hans Morgenthau. Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace,

rev. by Kenneth W. Thompson (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1985), p. 5.

8. Herbert Simon. Models of Man (New York: John Wiley, 1957), p. 3.

9. Balance Theory. Congruity Principle and Affective-Consistency Approach are

the three theories that are commonly encompassed by the rubric Cognitive

Consistency Theory. Although there are significant differences between these

theories, their overall arguments are quite similar. Here we focus on their

similarities. For a detailed discussion of their differences and similarities,

see Theodore M. Newcomb, Theories of Cognitive Consistency (Chicago. IL: Rand

McNally. 1968).

10. Other cognitive theories include attribution theory and cognitive

consistency theory. For a discussion of these theories and their applications,

see Hybel, How Leaders Reason, and earlier versions of this paper cited at the

start of the endnotes.

11. For a detailed discussion of the role played by the "Yenan Way" script, see

Immerman. CIA in Guatemala, pp. 104-5, 123, 127; and Hybel, How Leaders Reason.

12. See Newcomb. Theories, p. 50.

13. Statement made by Eisenhower during a meeting of the National Security

Council on 30 April 1953. Quoted in Richard D. Challener, "The National Security

Policy from Truman to Eisenhower: Did the 'Hidden Hand* Leadership Make Any

Difference?." in Norman A. Graebner. ed., The National Security (New York:

Oxford University Press, 1986). p. 57.

14. Quoted in Richard A. Melanson. Reevaluating Eisenhower: American Foreign

Policy in the 1950s (Urbana. IL: University of Illinois Press. 1987), p. 43.

15. Quoted in Stephen G. Rabe, Eisenhower and Latin America (Chapel Hill, NC:

University of North Carolina Press, 1988), p. 30.

16. Quoted in Branyon and Larson, Eisenhower Administration, p. 311.

17. See Immerman, CIA in Guatemala, p. 48; and Hybel, How Leaders Reason, p. 53.

18. United States Department of State. "A Case History of Communist Penetration:

Guatemala." (Washington, DC: US Government

Printing Office, 1957), p. 17.

19. Hybel, How Leaders Reason, pp. 57-58.

20. Ibid., pp. 58-59.

21. See Rabe. Eisenhower and Latin America, p. 49.

22. "Memorandum of Conversation by the Ambassador in Guatemala." (Schoenfeld),

Guatemala City. 25 September 1952, FRUS. 1952-1954. The American Republics IV,

p. 1040.

23. Ibid., p. 1041.

24. Immerman. CIA in Guatemala, pp. 130-31.

25. Quoted in ibid., p. 133.

26. By May 1953, the Arbenz government had redistributed some 740,000 acres.

27. "Draft Policy Paper Prepared in the Bureau of Inter-American Affairs." 19

August 1953. FRUS. The American Republics. FV, p. 1084.

28. Hybel. How Leaders Reason, p. 63.

29. Cole Blasier, The Hovering Giant (Pittsburgh. PA: University of Pittsburgh

Press. 1985). p. 161.

30. Immerman. CIA in Guatemala, p. 155.

31. Ibid., p. 165.

32. Blasier, Hovering Giant, p. 134.

33. Herbert S. Klein. Parties and Political Change in Bolivia, 1880-1953

(London: Cambridge University Press, 1969). p. 198.

34. Ibid., pp. 160-61.

35. Quoted in Klein. Parties and Political Change, p. 230.

36. Robert J. Alexander. Bolivia: Past, Present and Future of Its Politics (New

York: Praeger, 1982).

37. Ibid., 68-69.

38. Herbert S. Klein, Bolivia. The Evolution of a Multi-Ethnic Society (New

York: Oxford University Press, 1982). p. 213. See also James Malloy, Bolivia:

The Uncompleted Revolution (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press,

1970), p. 115.

39. Alexander. Bolivia, p. 70.

40. Pan of the fear has been attributed to the fact that Argentina recognized

the new Bolivian government immediately. See Alexander. Bolivia, p. 71.

41. Blasier. Hovering Giant, p. 47.

42. Ibid., p. 48. Paradoxically, after the United States extended its

recognition, President Villarroel appointed Victor Paz Estenssoro Minister of

Finance, and Washington did not voice its opposition. See Alexander, Bolivia, p.

72.

43. For a discussion of the negotiations, see Blasier, Hovering Giant, p. 50-51.

Victor Andrade, who was to play a critical role in persuading the Eisenhower

administration that the Paz Estenssoro government was anti-communist, was the

principal Bolivian negotiator in Washington in the 1940s trying to convince its

leaders not to side with the tin mine owners.

44. Quoted in Blasier, Hovering Giant, p. 52.

45. Klein. Parties and Political Change, p. 400.

46. Ibid., p. 401.

47. "Secretary of State (Acheson) to the Embassy in Bolivia," 8 September 1952.

FRUS. 1952-1954. The American Republics. IV., p. 503.

48. Alexander. Bolivia, p. 81.

49. Ibid., pp. 82-90.

50. Quoted in Sanders. "Quiet Experiment." p. 25.

51. Quoted in Bryce Wood, The Dismantling of the Good .Neighbor Policy (Austin,

TX: University of Texas Press. 1985). p. 157. Emphasis added.

52. See Immerman. CIA in Guatemala, p. 105.

53. Ibid., pp. 104-5.

54. Quoted in ibid., p. 138.

55. Quoted in Rabe. Eisenhower and Latin America, p. 24. By this time Dulles was

already convinced that Guatemala was one of the countries targeted by the

communists. See note 2.

56. President George Bush learned in 1990 how costly it can be for a president

to be advised by the wrong people, when he accepted Prince Bandar bin Sultan's

explanation as to why Iraq would not invade Kuwait. See Hybel. April 1993

version of tliis paper, (1993), p. 31.

57. "Memorandum of Conversation . . .," 25 September 1952. FRUS, The American

Republics, IV, p. 1040.

58. "Draft Policy Paper . . .." 19 August 1953, FRUS, The American Republics,

IV, p. 1084.

59. FRUS. The American Republics. IV, p. 1096.

60. See Hybel. How Leaders Reason, p. 63.

61. Immerman, CIA in Guatemala, p. 156.

62. FRUS, The American Republics. IV. p. 1123.

63. Argentina faced a similar problem during the Second World War.

64. On 10 January 1944, less than a month after Villarroel had been installed as

Bolivia's new president with the assistance of the MNR, Secretary of State

Cordell Hull contended, in a confidential memorandum, that the Axis controlled

MNR activities and had granted financial support to its leaders. See Blasier,

Hovering Giant, p. 48.

65. Blasier arrives at the same conclusion when he states: "Having suffered the

ordeal of nonrecognition in 1944, the MNR leadership made a great effort from

the very first moments after the insurrection succeeded on April 12. 1952. to

calm U.S. fears and pave the way for early recognition ..." See Cole Blasier.

"The United States and the Revolution," in James M. Malloy and Richard S. Thorn,

eds.. Beyond the Revolution: Bolivia Since 1952 (Pittsburgh, PA: University of

Pittsburgh Press. 1971). p. 64.

66. Quoted in James Dunkerley. Rebellion in the Veins. Political Struggle in

Bolivia. 1952-/982 (London: Verso Editions. 1984). p. 42.

67. Ibid., p. 41.

68. See Blasier. Hovering Giant, p. 50.

69. Ibid., p. 136.

70. Victor Andrade. My Missions for Revolutionary Bolivia. 1944-1962

(Pittsburgh. PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1956). p. 134.

71. Ibid., p. 12.

72. Ibid., p. 131. Being a Washington insider, it would have been impossible for

Andrade not to notice how much US foreign policy makers had opposed Guatemala's

land reforms.

73. Blasier. Hovering Giant, p. 136.

74. See Andrade. My Missions, p. 172.

75. Blasier. Hovering Giant, p. 134. Another person who played a critical role

was Dr. Carter Goodrich, an economist at Columbia University. Goodrich had been

invited to visit Bolivia as head of an United Nations technical mission. He

arrived shortly before the revolution and. thus, was able to establish contacts

with some of its leaders, especially Hernan Siles Suazo. After the MNR had

assumed power, he made it a point to ensure that Washington would grant

diplomatic recognition to the new government. One could speculate that he might

have known or met Dr. Milton Eisenhower, the president's brother, who was also

an academic and became the president of Pennsylvania State University in 1953.

It is also helpful to keep in mind that Goodrich was at Columbia while Dwight

Eisenhower served as Columbia's president between 1948 and 1950, and that the

two might have known each other.

76. Milton Eisenhower, The Wine is Bitter (New York: Doubleday, 1963). pp.

67-68.

77. "The Secretary of State to the Director of the Foreign Operations

Administration (Stassen)." 2 September 1953, FRUS, The American Republics, IV,

p. 535.

78. Blasier. Hovering Giant, p. 134.

79. Ibid., p. 135.

Ingrid Flory recently graduated from Connecticut College and is presently

studying in Guatemala.

Alex Roberto Hybel is Dean of National and International Programs and Robert J.

Lynch Professor of Government at Connecticut College.