The New York Times, June 30, 2004 pA16

Paralyzed by a Gun, Boy Now Seeks to Buy Maker.

(National Desk) Fox Butterfield.

The California attorney general's office has intervened in a

federal bankruptcy trial in a way that could help a teenager buy out

and shut down the manufacturer of a semiautomatic handgun with a

design flaw that has left the boy paralyzed from the neck down since

the age of 7.

In a highly unusual action, Randy Rossi, director of the firearms

division of the California Department of Justice, wrote to a federal

bankruptcy judge in Florida yesterday that Paul Jimenez, the man the

judge tentatively approved to buy the manufacturer, was ineligible

to make guns because he lacked federal and California firearms

licenses.

Therefore, Mr. Rossi wrote to the judge, Jerry A. Funk of United

States Bankruptcy Court, he was ''submitting this written objection

to the sale'' on behalf of the California attorney general, Bill

Lockyer.

Mr. Lockyer's intervention could benefit Brandon Maxfield, now

17, who was accidentally shot through the chin and spine in 1994

when his baby sitter tried to unload a .38-caliber Bryco handgun

owned by Brandon's parents.

Last year Brandon and his lawyer, Richard Ruggieri, won a record

$24 million jury award in Alameda County Court in Oakland, Calif.,

against the gun's manufacturer, Bryco Arms, and Bryco's founder and

the gun's designer, Bruce Jennings. The teenager and his lawyer

showed that because of a faulty design, the sitter had to turn the

safety off to unload the gun.

Now, after having helped force Bryco into bankruptcy proceedings,

Brandon and Mr. Ruggieri are trying to raise at least $150,000 to

buy out the company, one of the leading makers of inexpensive

handguns, known as Saturday-night specials, and melt down its

inventory of 75,000 handgun frames and slides.

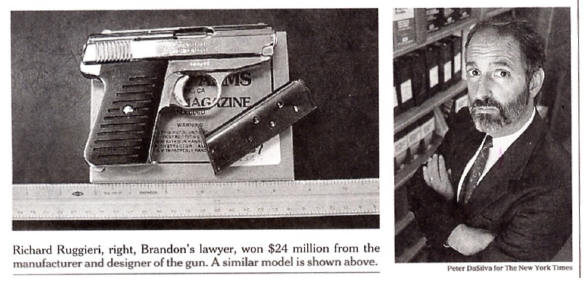

| Richard Ruggieri, right, Brandon Maxfield's

lawyer, won $24 million from the manufacturer and designer of

the gun. A similar model is shown. (Photo by Peter DaSilva for The New York

Times) |

|

Judge Funk gave tentative approval last week to the sale of

Bryco's machinery for $150,000 to Mr. Jimenez, a former Bryco plant

manager who Mr. Ruggieri claims is simply a stand-in for Mr.

Jennings. But Judge Funk allowed 20 more days for objections and

left open the possibility of higher bids.

''The attorney general's action could give us more time to raise

money and make a higher offer,'' Mr. Ruggieri, of San Rafael,

Calif., said.

But Mr. Jennings's lawyer, Ned Nashban, of Boca Raton, Fla.,

said, ''The attorney general is barking up the wrong tree.'' Judge

Funk, Mr. Nashban said, is only deciding who will buy the company,

not whether the new owner will manufacture guns.

''Mr. Jimenez could use the machinery to make widgets,'' Mr.

Nashban said.

Neither Mr. Jennings nor Mr. Jimenez responded to messages left

on their answering machines, but Mr. Nashban strongly denied any

collusion between the two men. ''I am not aware of any deal between

Jennings and Jimenez,'' Mr. Nashban said.

Mr. Ruggieri said he believed Mr. Jennings ''is just flipping the

business over as he has done in the past.''

In 1986, after losing an earlier lawsuit, Mr. Jennings sold his

gun manufacturing company to his manager at the time, only to

re-establish the business later, said Dr. Garen Wintemute, director

of the Violence Prevention Research Program at the University of

California, Davis.

In their effort to buy out Bryco, Brandon and Mr. Ruggieri have

taken the name Brandon's Arms and appealed for donations on a Web

site. They have also asked for contributions from gun-control

groups, celebrities and politicians with strong antigun views,

though with little success so far.

''I was very naive about it,'' said Mr. Ruggieri, who gave up his

law practice three years ago to represent Brandon full time. ''I

thought here was a concrete chance to actually do something about

stopping gun violence, not just make a donation to some

politician.''

An official for the Brady Center to Prevent Gun Violence said the

center's president, Michael Barnes, had been approached to give

money to Brandon's Arms but declined to do so. ''Obviously no one

wants to see Bryco back in business under any name,'' said the

official, who said the organization had limited resources and was

gearing up for a fight in Congress over renewing the assault-weapons

ban. Brandon has received a payment of $3 million from one of Mr.

Jennings's three ex-wives, as well as $5.75 million from the

insurance companies for an unrelated gun distributor.

But he does not have much money to buy Bryco, Mr. Ruggieri said.

First, he said, Brandon must reimburse Medi-Cal, California's state

health care system, $1 million, and there were $500,000 in expenses

for the trial, for expert witnesses, depositions and travel, Mr.

Ruggieri said. He would not disclose his fee, set by the court. The

rest of the money has been deposited in a trust for Brandon's

lifetime medical care, estimated at $11 million, and his education.

Collecting the judgment against Mr. Jennings has been complicated

by his efforts to protect his assets.

In a 1999 interview in Business Week magazine, Mr. Jennings

described his strategy for dealing with lawsuits against his

companies: ''They can file for bankruptcy, dissolve, go away until

the litigation passes by, then re-form and build guns to the new

standard -- if there is a new standard.''

Mr. Jennings not only controls Bryco, the gun maker, but also B.L.

Jennings Inc., which distributed the guns; seven trusts in the names

of his three children; and a string of luxury boats, cars and

planes, Mr. Ruggieri has said in court documents.

In 2002, shortly before Brandon's case went to trial, Mr.

Jennings, who lived in Southern California and Nevada, traveled to

Florida to consult with Mr. Nashban, a bankruptcy lawyer, on what

Mr. Nashban has described as estate planning.

Within a few days, Mr. Jennings bought a house in Daytona Beach

for $950,000 and an annuity for $500,000, according to the

bankruptcy court records. Under Florida law, people sued for

bankruptcy can protect the entire value of their houses and in many

cases their annuities.

Mr. Jennings sold Bryco's factory building in Costa Mesa, Calif.,

to a real estate company, Knowleton Communities Inc., for $4

million. The money was deposited in some of the seven partnerships

in the names of Mr. Jennings's three children, Mr. Ruggieri has said

in court documents.

In a deposition for the bankruptcy proceedings, Mr. Jimenez said

he would buy Bryco with a loan from Knowleton Communities.

Mr. Nashban, Mr. Jennings's lawyer, said his client's purchase of

a home in Florida and the annuity were ''prudent estate planning to

protect his family from his business. Anyone in a high-risk business

does that.''

Mr. Ruggieri has objected to Judge Funk's decision to allow the

proceeds of the sale to Mr. Jimenez to be deposited in the bank

account of Mr. Nashban's law firm, Quarles & Brady, rather than a

neutral party.

''Here's the guy who advised Jennings on how to hide his assets

now being in charge of holding the money to pay the creditors,'' he

said.

The federal bankruptcy trustee in Jacksonville, Felicia Turner,

filed a motion with Judge Funk on Monday supporting Mr. Ruggieri's

complaint.

Last week Brandon was in Children's Hospital in Oakland, Calif.,

for what he said in a telephone interview was a ''very minor''

operation, a skin graft to relieve a pressure sore.

Brandon is in high school in Willits, in Northern California,

where he lives with his mother and father. He is hoping to be

admitted to the University of California, Davis, to study marine

biology or paleontology.

Brandon said he harbored no personal grudge but wonders of Mr.

Jennings, ''How can he look at himself in the morning, knowing some

kid is going to be injured by one of his guns?''

|