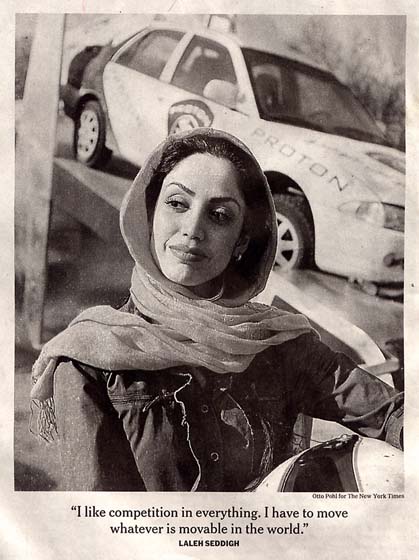

Only last fall 28 year old

Laleh Seddigh petitioned for the right to compete against Iranian men in auto

races. In March she won the national championship, agreeing not to wave to the

crowd of largely women fans, whose enthusiasm at her past appearances had

unnerved the organizing committee.

The New York Times, May 14, 2005 pA4(L)

Vroom-Vroom, She Said to the Doubters. (Foreign

Desk)(THE SATURDAY PROFILE)(Laleh Seddigh) Karl Otto Pohl. Full Text:

COPYRIGHT 2005 The New York Times Company

| LALEH SEDDIGH stepped on the gas, cut off a truck and blasted her Peugeot

between two other cars. ''I prefer to drive by myself,'' she said, seeing her

passenger steadying himself with a hand on the dash. ''In case something happens

-- it's a very big responsibility.''

With that, she broke around a blue pickup, accelerated past an Oldsmobile and

swerved onto an offramp, past a billboard of Ayatollah Khomeini and a 30

kilometer an hour speed-limit sign, doing 80 k.p.h., or just under 50 miles an

hour.

Ms. Seddigh loves speed. She also loves a challenge. Last fall, she

petitioned the national auto racing federation in this male-dominated society

for permission to compete against men. When it was granted, she became not only

the first woman in Iran to race cars against the opposite sex, but also the

first woman since the Islamic Revolution here to compete against men in any

sport.

What's more, she beat them.

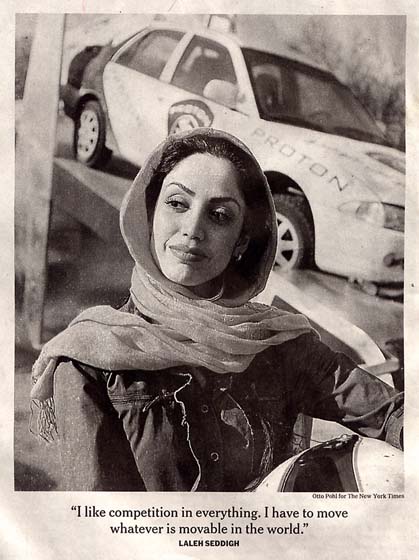

''I like competition in everything,'' the striking 28-year-old said after

parking the car and going for tiramisu in a cafe in North Tehran. ''I have to

move whatever is movable in the world.''

In March, she moved the nation when she won the national championship. State

television refused to show the new champ on the victory dais elevated above the

men, but photographers captured the moment. She stood quietly while receiving

her medal, as she had promised the race organizers she would, with a scarf over

her long black hair and a coat over her racing uniform.

|

|

Ms. Seddigh is a lively, energetic symbol of a whole generation of young

Iranians who are increasingly testing social boundaries. Seventy percent of

Iranians are under 35, and they have gently pushed for, and received, freedoms

unimaginable even a few years ago. For women in Tehran, at least, head scarves

are often brightly colored and worn loosely over the hair. The obligatory

women's overcoats are now often tight and short.

She admires the Formula One star Michael Schumacher -- in fact, the petite

Ms. Seddigh is often called ''the little Schumacher'' -- but her real hero is

her father, a wealthy factory owner. ''I've always wanted to be like him,'' she

said. ''Basically, he's my trainer in everything.''

''I want to show my father that I can do anything,'' she said. ''I've always

wanted to follow him. He drove fast and careful, and I looked up to him and

followed him. From the time I was 12 or 13, I wanted to have a competition with

boys, and maybe that was the reason.''

Ms. Seddigh is the oldest of four children. When she was 13, her father

taught her to drive on weekends in a park on the outskirts of Tehran. At 23, she

began racing miniature race cars that had more in common with go-carts. She also

entered three-day cross-country car rallies, in which she had to change her own

tires and make her own repairs. ''I had to do everything by myself,'' she said,

''because my navigator was a girl as well.''

THE opportunity to compete against the boys came last year, when a new

president took over at the Iranian racing federation who was open to allowing a

woman to enter the men's races. There has been a lot of jealous grumbling from

many of the male drivers, Ms. Seddigh said, but others, like Saeed Arabian,

Iran's previous national champion and now her driving coach, are proud of what

she has achieved.

''She is brave in asking for her rights,'' Mr. Arabian said. ''She will have

a great future.''

After winning the national championship, Ms. Seddigh was featured on the

cover of Zanan, Iran's largest women's magazine. (Zanan is the Persian word for

women.) Still, she is careful not to assume an activist's role.

''I'm not a feminist,'' she said. ''But why should women be lazy and weak? If

you're determined, you've got to push.''

She has been pushing into traditionally male pursuits all her life. With her

father's encouragement, she has devoted her academic career to preparing to

succeed him in the family business. She received a bachelor's degree in

industrial management and a master's in production engineering, and is now

working on her Ph.D. in industrial management and production, all at Tehran

University.

She enjoys her studies, she said, but driving is her first love. It appears

to be a widely shared passion, as the exuberantly chaotic traffic of Tehran

makes competitive driving seem like a national sport. Drivers barrel into any

slightly open stretch of pavement, three-lane roads often have five cars abreast

and sidewalks are fair game. Traffic lights count down the seconds before

turning green, adding to the racetrack feel.

''Tehran is a great place to learn how to drive,'' she said.

It is also a good place to have an accident. She has wrecked two cars in the

city's traffic.

Her driving has caused frequent arguments in her family, she said. After all,

she broke her neck in one accident on the racetrack, and her left leg has metal

screws in it from another wreck. Her father supports and finances her racing

habit but, with her neck injury, he recently forbade her to race the

rough-and-tumble go-carts.

''He knows I love driving, but wants me to be careful,'' she said. Her mother

has learned to stay out of it. ''She was just crying, praying, nothing more.''

Despite the difficulties at home, Ms. Seddigh enjoys shocking her family with

her exploits. She has a photo on her mobile phone of the speedometer topped out

at nearly 150 m.p.h. -- ''so my family would believe it,'' she said of a recent

drive on an expressway in Tehran.

It is only in recent years that women have even been allowed to watch men's

sports. At her first race, women were screaming and climbing up the fences, Ms.

Seddigh said, and that worried the organizers. ''The committee said, 'Please,

don't make the audience excited,''' she said. For the championship, she had to

agree not to wave to the crowd, a third of whom by this point were women.

Last year Ms. Seddigh was sponsored by Proton, a locally assembled Malaysian

car, but she hopes to get a more prestigious international sponsor for the

coming season. Subaru offered her a sponsorship but required her to move

overseas, which she does not yet want to do. But she realizes that she may have

to, at some point: car racing in Iran does not draw big money. Her victory last

month netted her a medal, a winner's cup and a certificate of achievement.

She is currently preparing for the next season, working out daily and racing

several days a week. She is also helping teach a training class for women who

are race-car drivers, the first in the country.

''I've got maybe five or eight years of driving left,'' she said. ''When you

get old, you have to calm down.''

But that is still far in the future. For now, she is still busy dusting

competitors and trailing speeding tickets. She is doing it for herself, she

said, but then she twirled her tiramisu spoon and saw a broader theme.

''In this society, women don't believe in themselves,'' she said. ''They have

to believe in their inside power.''