The New York Times, June 2, 2004 pA11

Where Butterflies Rest, Damage Runs Rampant. (Foreign Desk) Ginger Thompson.

Full Text: COPYRIGHT 2004 The New York Times Company

|

The New York Times, June 2, 2004 pA11 Where Butterflies Rest, Damage Runs Rampant. (Foreign Desk) Ginger Thompson. Full Text: COPYRIGHT 2004 The New York Times Company |

|

The illegal loggers smeared mud on their faces to hide their identities. Then they smashed a camera they feared would expose their pillaging.

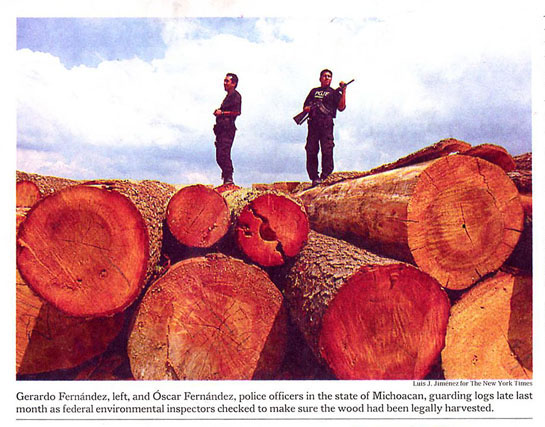

The evidence, however, was everywhere. Two trucks rumbled down the mountain with illegally cut wood. The mud-smeared loggers had fresh blood under their fingernails from loading. In a federally protected forest that is a winter haven for the monarch butterfly, the landscape was as barren as the moon.

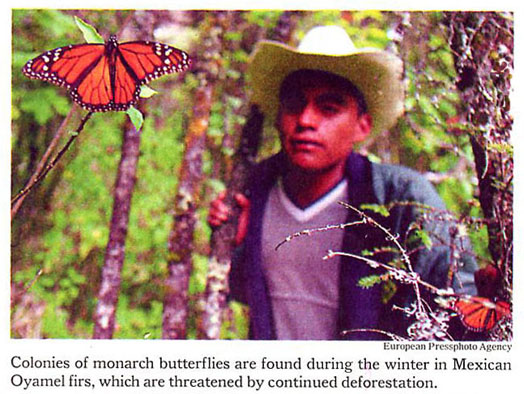

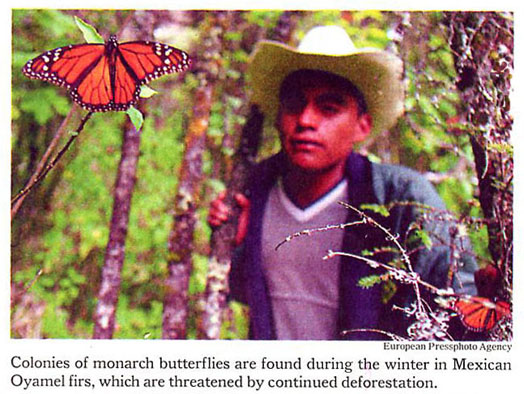

This is Mexico's most famous national park, a 10,000-year-old evergreen forest set aside by presidential decree and supported by millions of dollars in international aid for colonies of orange and gold butterflies that migrate annually from the United States and Canada, in clouds that look like fire in the sky.

But when the butterflies leave each spring, and the hundreds of thousands of tourists go home, this reserve stretching west from the suburbs of Mexico City to the mountains of Michoacan becomes a symbol of the rapid destruction of all the nation's forests, and is overtaken by organized crime and mob justice. Heavily armed mafias chop down the trees at an alarming rate -- about 70 mature trees each day, or a small forest a week, Mexican authorities say.

The mobs ambush the police and terrorize village leaders who threaten to stop them. Left alone to defend their property, some beleaguered villages take the law into their own hands to fight back against the loggers, often using the same violent tactics. Most villages surrender and sell their trees.

The illegal logging, peasant leaders say, is driven by a surging demand for wood; by the crushing poverty of the Indians who live in communal cooperatives, called ''ejidos''; and by the lingering resentment over the government's decision 18 years ago to turn the precious forests into a reserve for insects that their people refer to as ''worms.''

Indeed, the mud-smeared men of San Luis spoke with contempt for a society they say cares more about the butterflies than about their families. This land belongs to them, they said, and they would not surrender their rights to a presidential decree, much less forsake the needs of their children for bugs. ''Everyone worries about the butterflies,'' said one illegal logger, the brim of his baseball cap pulled to his nose to hide his face. ''What about us?''

Then the loggers lashed out against a group of journalists. They smashed a photographer's camera, punched a radio reporter in the face, and threatened to hold the group hostage, accusing the journalists of being government spies. The smell of alcohol made their voices more menacing. ''We are not going to hurt you,'' they said. ''We are thieves, not savages.''

The police and government environmental inspectors have also been attacked, and rarely venture into villages like San Luis, unless they do so en masse and in military style. Officers and inspectors have been detained for hours by criminal mobs that set their vehicles on fire. The loggers have staged roadblocks to take back trucks of wood that had been confiscated by the police; and stormed jails to free their leaders.

Inundated by pleas from communities like this one and by calls of outrage by international environmental organizations, including the World Wildlife Fund, President Vicente Fox sent the army into the forest in May to restore order. ''We are at war,'' said Gabriel Mendoza Jimenez, deputy secretary of public security for the state of Michoacan. ''This is not only a problem of cops and robbers. This is a fight for civil order over impunity.''

| Victor Lichtinger, a former minister of the environment, said that in much of

the world including most of Mexico, deforestation remains a largely quiet

phenomenon, spreading almost a tree at a time, and driven by the poverty of

rural farmers who cut down small plots of the forest to make way for subsistence

crops. But Mexico's forests, he added, are also the strongholds of drug

traffickers and armed rebels. They are seething with tensions from unresolved

land disputes that go back generations. They are far removed from the reaches of

the law.

From the day the government established the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve, peasants here have lived at odds with the government, and the deforestation turned fast and turbulent. Mexico had given this land to peasants from the spoils of the revolution. With the creation of the reserve in 1986, the peasants accused the government of taking their land away. |

|

The people of San Cristobal, at the southern edge of the butterfly reserve, burned down their trees, rather than cede control to the government. Fourteen years later, the Mexican government expanded the reserve to more than 132,000 acres from 45,000 acres, offering peasants who live in extreme poverty few economic incentives to save their trees. The tensions, and deforestation, spread.

Now, as the demand for wood grows in factories, construction companies and fruit packing plants, middlemen have moved into the forests offering good money for timber -- about five times the average daily wage for a 60-year-old pine -- and peasants have decided to do business.

''What was once a problem of poverty and a necessity to survive has turned into a crime of greed,'' Mr. Lichtinger said, speaking of the logging in the butterfly reserve. ''There is no way to get the mafias to submit to the law.''

Governor Lazaro Cardenas Batel said, ''If we tell people they cannot exploit their forests, and walk away, then we condemn them to dying of hunger, or we force them to become involved in illegal logging.''

The governor said the growing tensions in the butterfly reserve were one result of a three-year-old crackdown against industries around the area that buy illegal wood. Some 100 sawmills had been closed or fined, he said, and 159 people had been arrested, most of them poor workers.

But in a state with four million people, fewer than 9,000 police officers and a flourishing illegal marijuana trade, the governor acknowledged he could only crack down so hard. He said he was reluctant to send officers chasing illegal loggers in the forests because he worried about ''confrontations with peasants that get out of control.''

He said he supported President Fox's decision to send the military.

Mr. Mendoza, the public security official, agreed. ''I could send officers into the forests and lose three of them a day,'' he said, ''but I am not willing to make that sacrifice.''

Federal environmental authorities are also strapped for money and manpower. Unlike the United States, where nearly 2,000 permanent and seasonal armed rangers patrol 387 national parks, Mexico's protected areas are hardly protected at all, with fewer than 400 roving, unarmed inspectors assigned to watch over 150 natural reserves.

Diana Ponce, a deputy prosecutor for Profepa, the agency charged with protecting Mexico's natural resources, said peasants are ravaging forests from Chihuahua to Chiapas. She estimated that the country loses about 1.3 million acres of forests each year, the fifth worst deforestation rate in the world.

Some 70,000 acres are cut down each year from the Lacandon rain forest, home of the Zapatista National Liberation Army and the hemisphere's most biologically diverse jungle after the Amazon. Environmentalists predict it could disappear within the next two decades.

The old-growth pine forests in the northern Sierra Tarahumara and its rich diversity of wildlife face threats from drug traffickers who burn down the trees up to 200 years old to plant marijuana. Villagers who stand against the traffickers have been killed. Two peasant leaders, Isidro Baldenegro Lopez and Hermenegildo Rivas Carillo, were arrested last year without warrants. Amnesty International considers them prisoners of conscience, comparing their arrests to the government's abuses against the forest crusaders Rodolfo Montiel and Teodoro Cabrera of the state of Guerrero.

But no forest's plight draws more attention these days than the monarch butterfly reserve.

Homero Aridjis, a poet, author and leading Mexican environmentalist, said: ''The federal government has no control. The state government has no control. The forest has become a no man's land.''

The World Wildlife Fund reported two years ago that some 40 percent of the butterfly reserve had been destroyed from 1971 to 1999. Last month, the organization reported that more than 500 hectares have been lost in the last three years. Aerial photographs, the group said, showed that the villages of Francisco Serrato and Emiliano Zapata had lost all of their forests.

''I have climbed the mountains to ask my people why they are cutting the forests,'' said Alejo Claudio Cayetano, an Indian leader in the ejido, or community, of Cresencio Morales. ''They tell me that if they do not cut them, others will, and then they will have nothing.''

People in the ejido of El Paso fight hard to hold on to their forest. The camp of plastic tents beneath their towering pine and Oyamel firs is their battle station, manned by grandmothers and sons, who leave their homes five days a week to help guard the trees.

Last year, the leader of the ejido, Armando Sanchez Martinez, discovered a truck loaded with wood that had been illegally cut from their forest. He set it on fire.

Then a couple of months ago, after gunmen fired on his truck, Mr. Sanchez bought a handful of rifles and handguns and recruited the other ejido residents to serve on civilian patrols. Their support, he said, was unanimous.

''The illegal loggers wanted to shoot one of us to frighten us and take our forest,'' he said. ''Now they are going to have to shoot us all.''