Lawsuit Pressures State of California to

Provide for Schools

From the New York Times April 17, 2003......article by Jonathan Glater

(Scroll down for a more recent article - 8/13/'04

- reporting victory for plaintiffs)

California has spent $13 million in the last three years defending itself in

a lawsuit seeking to improve conditions in its public schools. And that figure,

which is likely to rise, has drawn attention as lawmakers face a looming budget

deficit.

"To spend $13 million on lawyers from Los Angeles instead of on education is

really a crime, said state Senator John Vasconellos, a democrat from San Jose.

Vasconellos said he had called the governor's office last week to find out how

the $13 had been spent and where it came from.

The class action suit puts governor Gray Davis in an awkward position. He has

announced initiatives to improve education, but his lawyers are arguing that

many problems should be dealt with by local school districts, not by the state

government in Sacramento.

| "A number of issues that have been

raised in the suit are issues that we feel the state is in the process of

addressing," said Kerry Mazzoni, the state's secretary of education. The

state government alone should not be responsible for enforcing standards in

schools, she said, arguing that school districts should share the burden."

Williams verses the State of California, the class action suit filed by

civil rights and other organizations on behalf of schoolchildren, claims

that the state has allowed students to attend schools in poor condition,

with untrained teachers and with inadequate resources. It says the students

in deprived schools are disproportionately non-white and that many are

learning English as a second language.

"The staggering range of disparity in public education in this state

offends the core constitutional principle of equality," the suit says. The

suit focuses on 46 public schools, describing things like teachers who lack

training, students forced to share textbooks, crowded classrooms and

unsanitary restrooms,"

"Lack of books, lack of teachers, lack of college counselors, there

weren't enough desks for the students, there weren't enough working

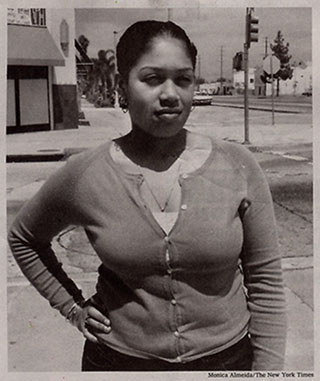

restrooms," said Cindy Diego, 19, a plaintiff in the suit. Ms.

Diego graduated in 2001 from John C. Fremont High School in Los Angeles and

has a sister there who has told her that conditions have not changed much,

but that now, "they have more working restrooms."

|

|

|

|

photo by Monica Almeida for the New York Times |

| Cindy Diego, 19, of Los Angeles, a

plaintiff in the suit, listed school problems like a lack of books, lack of

teachers and a shortage of desks. |

The state has acknowledged that there are problems, though not necessarily

the same ones at the same schools, but lawyers for the two sides have not been

unable to reach a settlement on how to improve them. Lawyers not involved in the

case said it should be possible to verify the problems and discuss remedies.

"My fear is that it's more expensive for the state to litigate than to make

the changes that are needed," said Robert E. Borton of the law firm Heller

Ehrman White & McAuliffe, which is not involved in the case. Mr. Borton said

that by the standards of litigation between large companies, the $13 million the

state has spent defending the suite, in which it is represented by an outside

firm, O'Melveny and Myers, is not an unusual amount. If the case goes to trial

the bill is likely to be several million more, he said.

Hilary McLean, the governor's spokeswoman, said Morrison and Foerster, a firm

representing the plaintiffs, was seeking legal fees from the state. Michael

Jacobs, a lawyer for the firm, said that it was working pro bono (for free)

and that any fees it collected would go into a fund for pro bono work.

Each side blames the other for failing to agree on how to improve conditions

in the schools. Ms Mazzoni said the coalition's demands were vague. We have

always wanted to settle this suit," she said, "and unfortunately we have not

gotten a clear idea from the plaintiffs of what it would take and what they

would really want." Lawyers for the plaintiffs said that they did present

detailed possible remedies and that the state showed little flexibility in

discussing them.

The lawsuit does not seek money, just a declaration that the state has the

responsibility to make sure that disparities in the schools are eliminated. As a

first step, Mr. Jacobs said, the government should determined the scope of the

problems, the cost of repairing them and the feasibility of paying such costs.

"For example, one of the you would want to know accurately is how many kids lack

textbooks," he said.

Ms. McLean said that "in a sense that's true," but that in some cases

teachers were using materials other than textbooks. And she said that the state

government should not bear the sole responsibility for verifying that every

toilet operates, that every classroom has a qualified teacher or that every

student has a textbook. Ms. Mazzoni said that supervision of such details should

be the responsibility of local school boards. "If the plaintiffs had their way,"

she said. "we would have a state bureaucracy that would have to go out to over

1000 school districts."

A lawsuit in the early 1990's undermines the state's argument that

responsibility should lie with the school districts, said Catherine Lhamon, a

lawyer at the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California, part of the

coalititon that filed the current lawsuit. In the earlier suit, Ms. Lhamon

noted, a local district with a money shortage had announced plans to close

early, but the California Supreme Court ruled that the state was ultimately

responsible for keeping schools open.

"The legal obligations of the state are sufficiently clear that we shouldn't

be arguing," Ms. Lhamon said. "It's really not open for the state to say it

doesn't have to make sure kids have textbooks, that the state doesn't have to

make sure that there's a teacher in every classroom.

......................................................................................................................................................................................................................

The article below appears to be about the lawsuit

discussed above. The plaintiffs appear to have won, despite $18 million spent by

ex-Governor Davis to fight the suit.

The New York Times, August 13, 2004 pA12

California Will Spend More To Help Its Poorest Schools.

(National Desk) Nick

Madigan.

Full Text: COPYRIGHT 2004 The New York Times Company

If 16-year-old Eliezer Williams has his way, rats will no longer scurry

through classrooms in California, and every student will have books, a place

to sit and a clean bathroom to use. Eliezer is the lead plaintiff in a

class-action lawsuit filed in 2000 by the American Civil Liberties Union on

behalf of 1.5 million California students, most from poor neighborhoods. The

lawsuit accused the state of denying poor children adequate textbooks,

trained teachers and safe classrooms.

Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, a Republican, plans to announce Friday that

California has settled the suit by agreeing to the demands that the students

receive equal access to basic instructional materials in all core subjects

and that they be taught by qualified teachers in sound and healthy schools.

The proposed settlement, which is subject to approval by a judge, would

require the state to devote as much as $1 billion to repairs and upgrades to

2,400 deteriorating, low-performing schools. It would also provide almost

$139 million for textbooks this year alone.

''This means that every child counts,'' said Mark D. Rosenbaum, legal

director of the Southern California branch of the A.C.L.U. The deal, Mr.

Rosenbaum said, ends ''decades of neglect and indifference.''

''We were in classrooms where kids had to share space with rats,'' he

said. ''We saw essays posted on a board in an elementary school where kids

had written about the prevalence of rats in their classrooms.'' While

touring schools to research the lawsuit, Mr. Rosenbaum said, he found

children who had defecated in class because restrooms were out of order. In

some classrooms, he said, rain poured through holes in ceilings.

Citing a Harris poll, Mr. Rosenbaum said that one million to two million

students did not have books for use in school or to take home for study, and

that schools with high concentrations of black and Latino students were 74

percent more likely than predominantly white schools to lack sufficient

textbooks.

In Eliezer's case, books were so scarce at the Luther Burbank Middle

School in San Francisco, which he attended when the lawsuit was filed, that

the books had to be shared, and teachers were forced to photocopy texts so

students could do homework. He said a dearth of desks meant that students

often had to push desks from one classroom to another. ''It was strange,''

Eliezer said in a telephone interview on Thursday. ''This is a pretty big

state and I thought we'd be able to afford enough books for everybody.''

He said the bathrooms were sometimes ''filthy and dirty'' and that

ceiling tiles were missing in the gymnasium, prompting fears that some of

the remaining tiles could fall and hit someone. In the locker rooms, he

said, doors were bent and locks broken. Eliezer said he took pictures of the

damage. The school he attends now, Balboa High School in San Francisco,

where he will be a senior in the fall, is ''a little bit better,'' Eliezer

said, but not perfect. ''The boys' bathroom was closed for half the year, at

least, last year,'' he said. ''It was out of order, flooded, just messed up.

It took time to fix.''

The administration of Gov. Gray Davis, a Democrat who was ousted last

year in a recall election, spent about $18 million fighting the lawsuit.

Lawyers for the state argued that poor students were unlikely to do

better in school even if they had the same educational benefits as children

who were not poor. They also said the responsibility for ensuring

educational equality belonged to local governments.

But the plaintiffs argued that the state had denied thousands of children

their fundamental right to an education under the California Constitution.

''Children who lack the bare essentials necessary for an education,''

said Mr. Rosenbaum, the A.C.L.U. lawyer, ''can hardly be expected to

achieve.'' |

| |

Article CJ120584589 |